Business

We polled the public on our IG and here are answers from the editors themselves!

EG: My process is pretty straightforward. I drop off film at the lab and they give me pretty big scans of the entire shoot in about 3 days. That goes into the computer and its just like a digital shoot at that point. If the client needs a bigger file, then I may do additional high res scans of the final files.

You have to communicate what this will look like to the client. I live in NYC, so I can run to the lab pretty much the same day and in 2-3 days have decent scans ready to go. But your location or post processing process may differ. I find that 2-3 days is not really a deal breaker for most situations.

Link to this anwser.

EG: For sure. I personally don’t like to mix too much because my brain gets confused, but if you can identify scenarios that you like for digital and others for film or just shoot a mix at all times, then go for it. I’ve definitely shot mostly digital before and when a situation is really hitting hard, then I grab the film camera. I’ve also brought my digital camera to use as a polaroid. Adjust. And then move to the film cameras. I’ve shot A LOT of film in my life, so I’m pretty confident in my cameras and my ability, but it’s ultimately about shooting a ton and believing in yourself!

Link to this anwser.

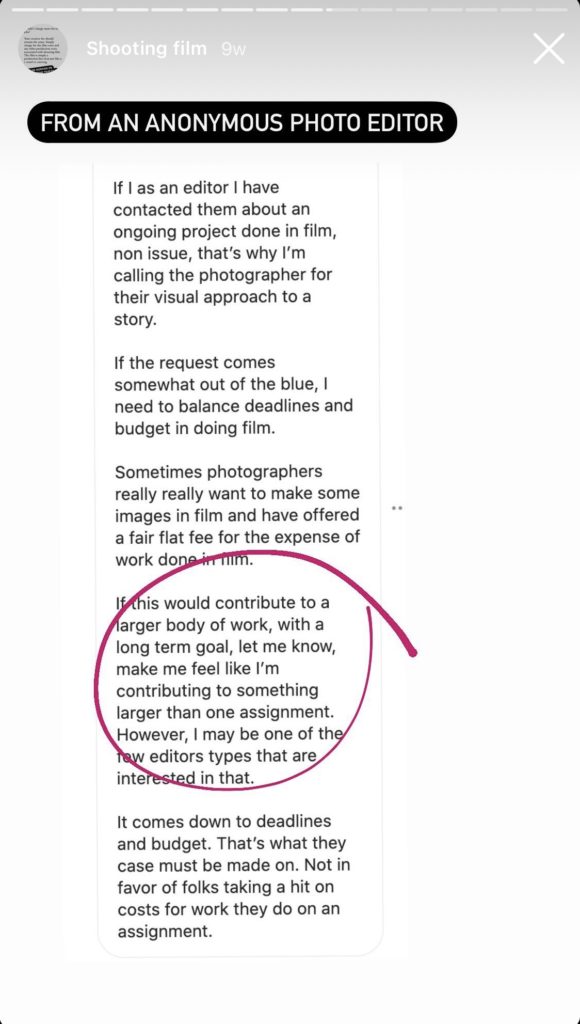

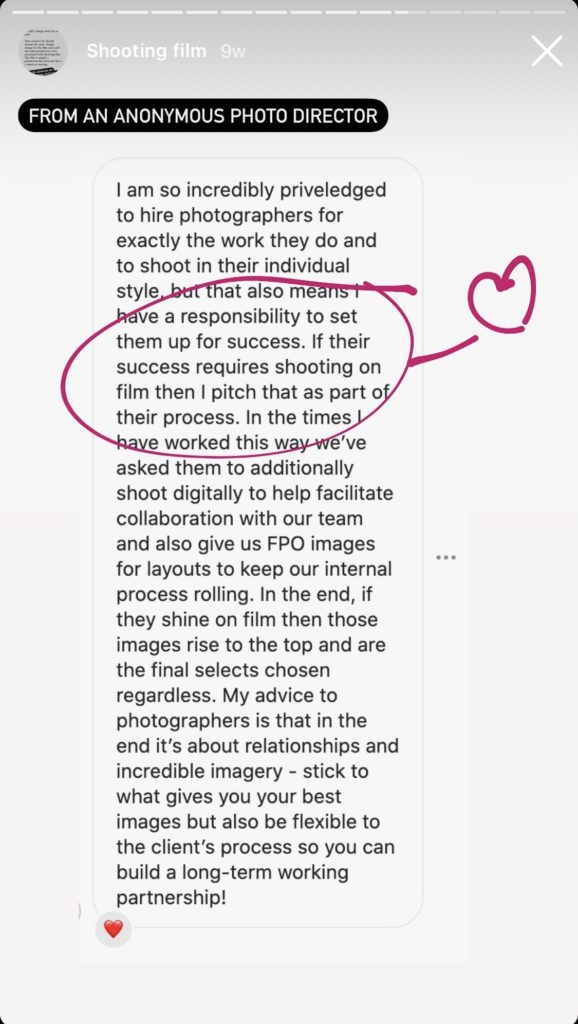

EG: First, let’s identify why I, personally, would want to shoot film on a job. For me, the combination of the cameras, the lenses, and the film ‘look’ create a certain picture quality that I still can’t really replicate with digital cameras. Also, I tend to shoot almost exclusively medium format film. Those cameras are slow and clumsy, so they force me to go into a mental zone that is hyper focused, methodical and way more intentional. I really enjoy that space and feel like the images are better, afterwards. Whether that’s true or not is 100% subjective, but that’s just how I feel. So if a job feels like it could yield some especially powerful imagery, I will try to shoot film if the logistics allow for it.

Everyone will have their own reasons for wanting to shoot film, and it’s important you identify why you’re even complicating things for yourself!

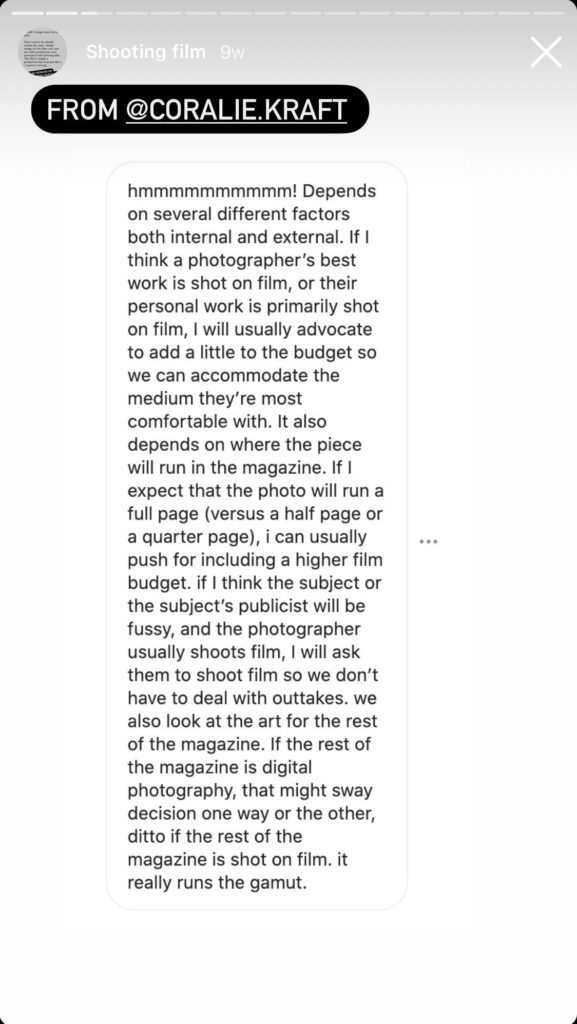

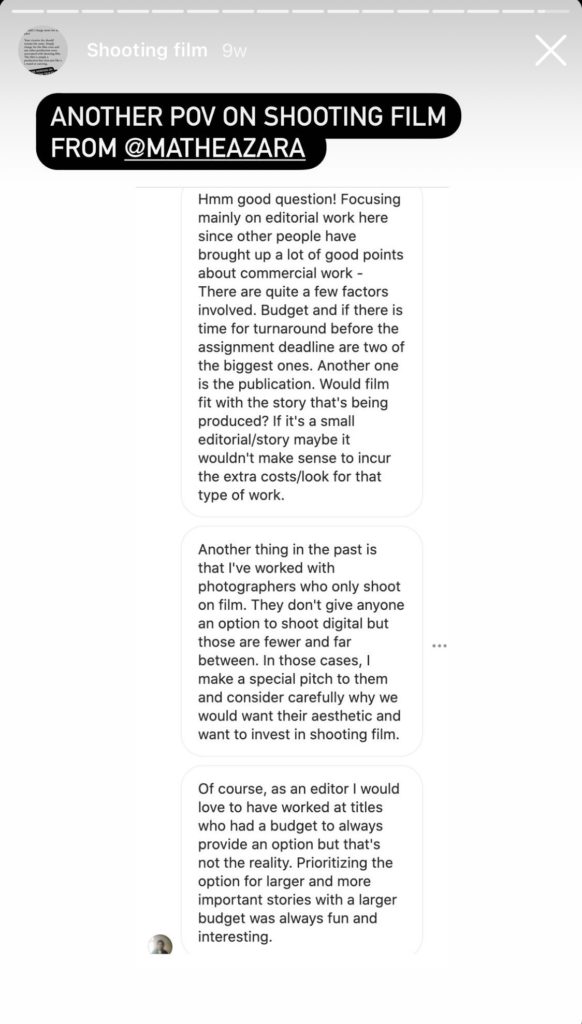

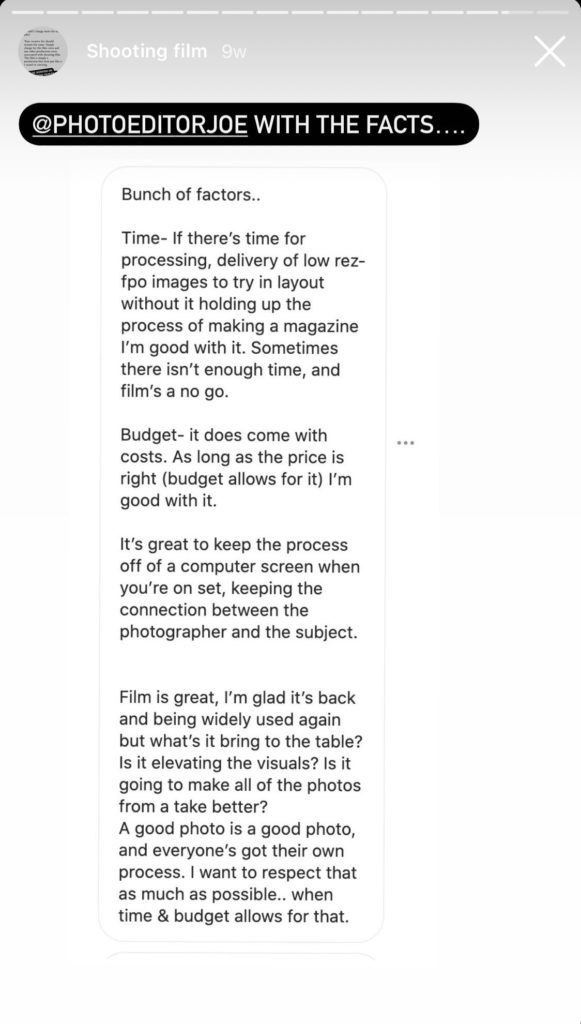

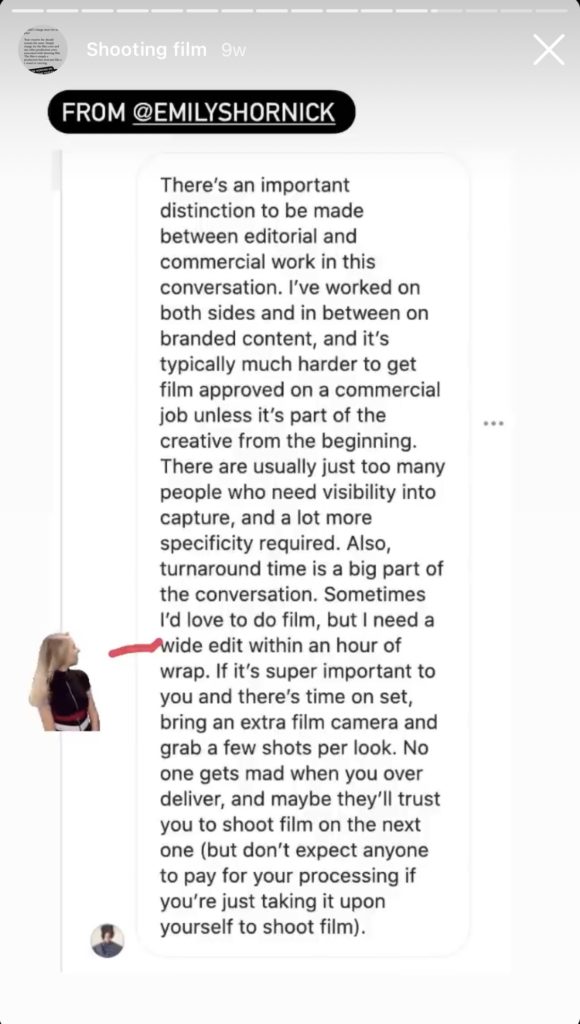

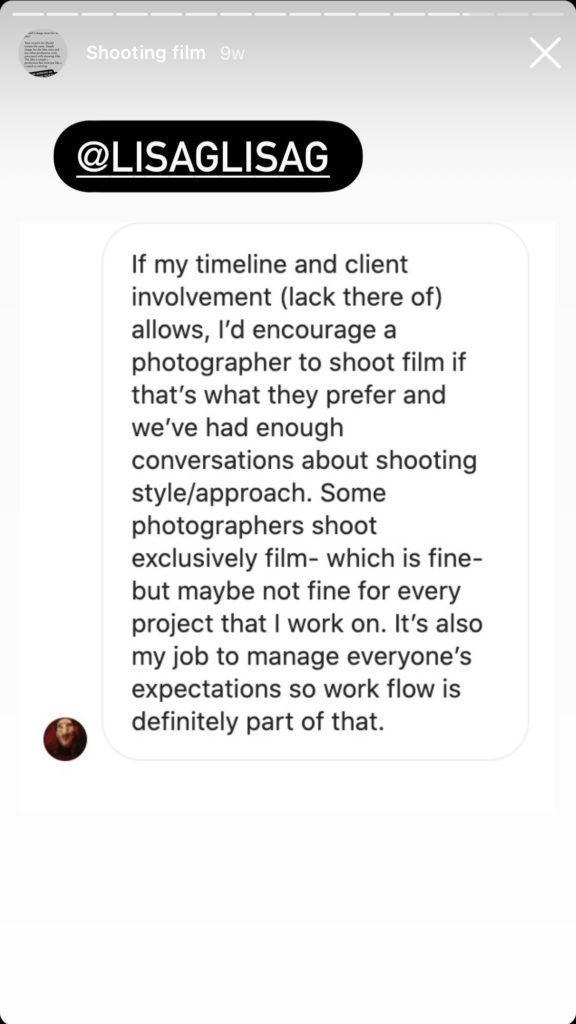

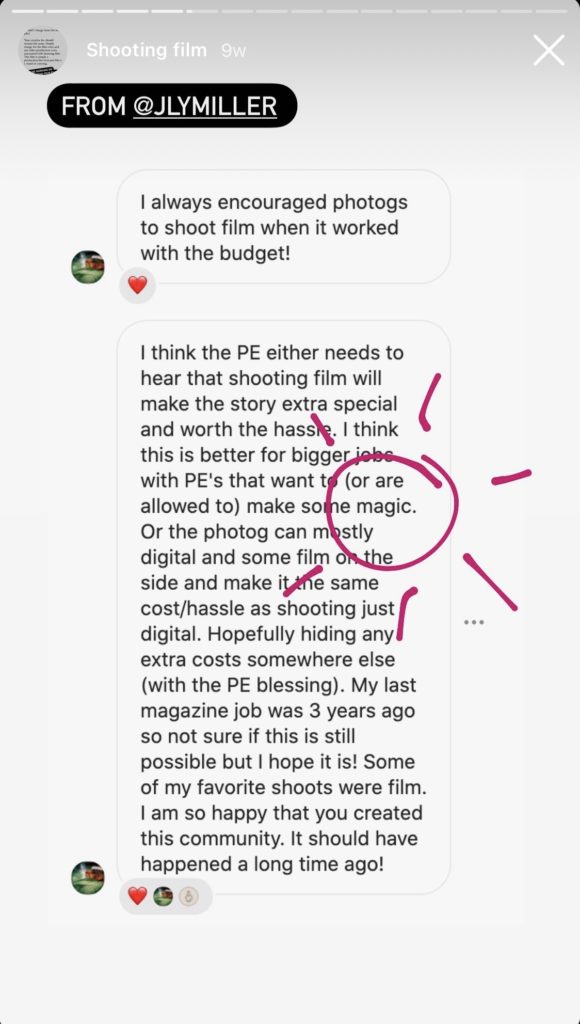

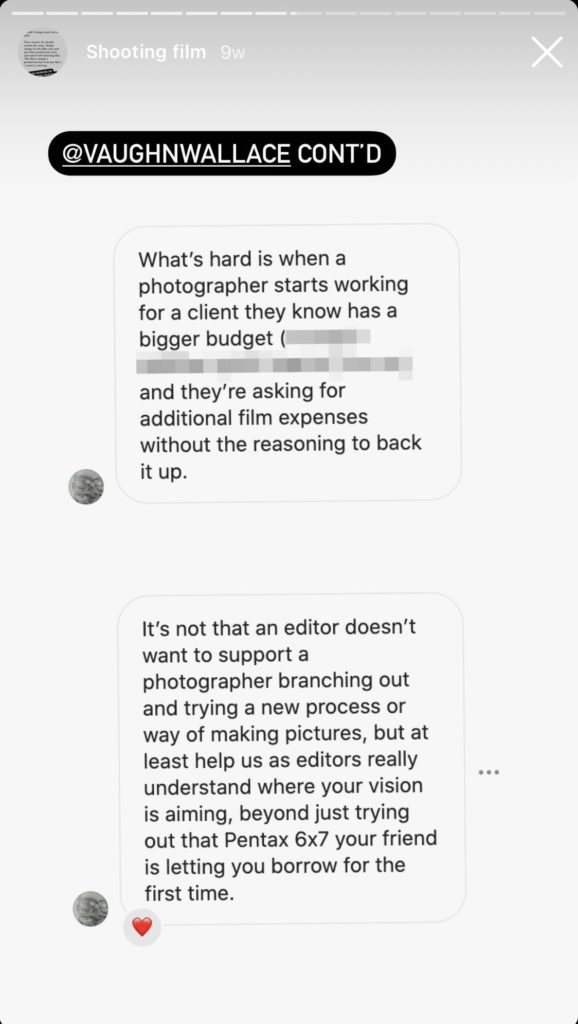

Once you identify that you’d like to shoot film for a certain project, now it’s time to get that approved by the client. Some clients will love the idea and embrace the added complications. For some clients/jobs, the answer will be ‘absolutely not.’ And maybe some jobs will allow for a hybrid shoot with some shots on film, but most on digital, or something like that. Every job will be different.

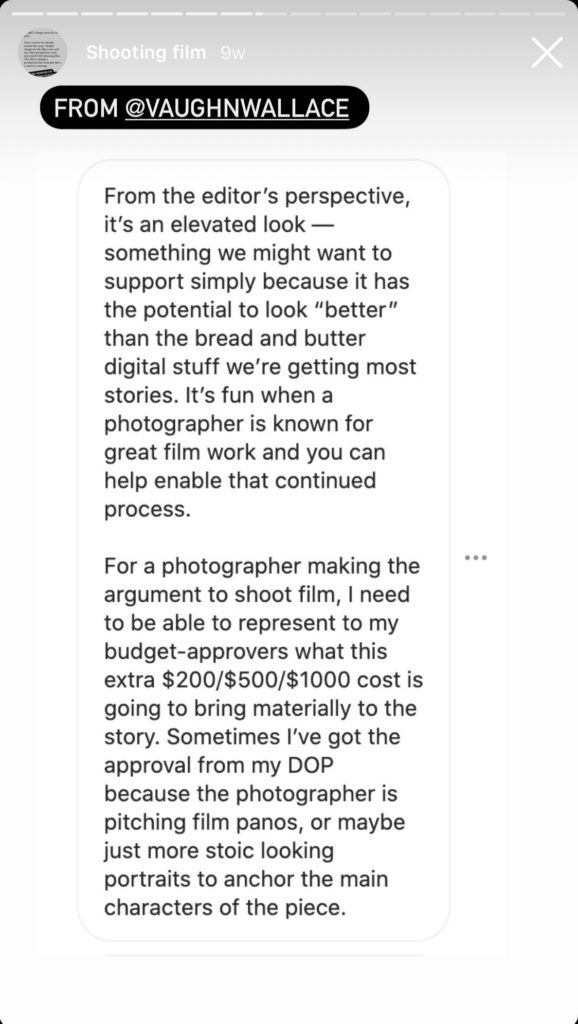

In order to get approval, you’ll most likely need to let the client know how much it costs and how much longer it will take to see images. This is really as straightforward as estimating how many rolls you will shoot, what that costs to buy/develop/print/scan and put that into an estimate. On bigger jobs, you may be able to add a little on top of those costs to cover the time to buy, run to lab, etc etc. Something like a 20% markup on top of the actual costs. For example, one roll of Kodak Portra 400 costs $10 to buy and $20 to develop and scan (medium res). If I anticipate shooting 10 rolls on a job, then it’s $30 x 10. You may need to add a high res scan on top of that or an actual c-print if that’s your process.

An example from an actual estimate below:

Example shows a 2-day shoot where I would rent two cameras and shoot an estimated 20 rolls of 120 per day @ $35/roll

Obviously, on a bigger shoot an added cost of $1900 is not that much. But for smaller shoots, it may be problematic.

Link to this anwser.

EG: I always think that whether you can figure out how to start assisting is essentially a litmus test of whether you’re gonna make it or not. The formula is pretty easy, tbh.

1. Find photographers you like.

2. Email them. Say hello. Tell them you like their work and you’d love to assist someday.

3. Don’t expect a response. If you get one, great.

4. Stay in touch a few times a year.

5. Repeat until you no longer want to assist.

There it is. That’s the secret to a career in photography. Research. Interact. Repeat. This works for assisting, for magazines, for commercial clients, etc etc. If you’re cool, or talented, or a hard worker, or really pleasant, or any combination of those, you’ll be fine if you follow this formula.

JS: An easy way to get started is to assist your friends, you will both learn quite a bit in the process and it’ll be low pressure since you know each other. Another way is to reach out to photographers in your area. Send them a polite email sharing your background and experience level along with a link to your website, conveying your interest in assisting. Join a professional organization such as ASMP or APA both have databases for assistants.

CC: Do what is suggested above and follow up. I started assisting by doing 1, 2, and 3. I’ll also add that I didn’t get any responses from the 30+ emails I sent and when I followed up with all of them I received a response from 2 people who I ended up assisting regularly for two years and learned a ton from (while also testing and assisting my friends – make friends with other photographers at your level at local photo events and you’ll level up together as time goes on). As Emiliano said, it’s important to stay top of mind and if a photographer’s usual assistant isn’t available and you happen to follow up on your email, you might get hired. The tricky part is not having all the experience necessary (or any experience) to be a first assistant so Jake Stangel created this super helpful video. I’d have to say that nothing compares to being able to play with all the gear IRL so I would also suggest reaching out to 1st assistants and asking if you can be brought on as a 2nd or 3rd assistant on bigger jobs. I learned so much this way – during downtime, the 1st assistant would show me how all the gear worked. You can also try to get into the equipment rooms at studios or rental houses to familiarize yourself with the gear and meet photographers that way.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Don’t. If you can avoid it.

Obviously, sometimes you gotta take the money or the project is something you really want to do. Try to negotiate and ask if there’s any flexibility on the terms or the budget.

JS: Contracts are always negotiable. Do the best to communicate that the terms are uncomfortable and overreaching, then propose a new set that are more favorable to you. Also, it’s more than okay to walk away.

CC: Sometimes clients want a buyout of images or WFH so they don’t have to deal with licensing. There’s an opportunity to ask how the images will really be used and negotiate to keep the copyright and discuss licensing. You get to decide whether it’s worth losing out on any opportunity for a license extension in the future or to license the body of work to a third party in the future. Some great advice here from Photo Bill of Rights.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Make the type of work you want to be hired to make.

CC: Agreeing with Emiliano here. Think of it from the client’s perspective – they’re making an investment in your eye, your images, and your ability to run your set and deliver on the brief. What is in your portfolio demonstrates what you’re capable of, so you’ll get hired for what you show. It’s the same reason I look at photos on yelp 🤤

JS: This is an evidence based industry, in order to get the work you want, you have to demonstrate that you are able to do it- consistently.

Link to this anwser.

EG: You have to approach this as a long-term thing. Just because a photo editor followed you on Instagram doesn’t mean you’re going to get a job. Just because they responded to your email doesn’t mean you’re going to shoot the cover. You’ll literally send hundreds of messages before getting your first jobs. You’re going to bid dozens of jobs and not get any of them. You’re going to spend many days writing treatments that you won’t win. You’re going to strike out a million times before you get any jobs. No one owes you a damn thing. It’s a slow, slow process, so bunker down for the long haul. The only thing that you can control is your creative output. Make sure it’s 🔥🔥🔥.

Some basic math: I may send out a newsletter to, say, 1000 people. Of those 1000 people, only about 100 of them will read it. Of those 100, only 25ish will respond with “great work!” And only about 1 or 2 of them will eventually hire me at some point. Maybe next month, but probably next year. The turnaround on success and ROI on any marketing is measured in years . . .not months and definitely not days. I’ve never walked out of a meeting knowing I was going to get a job from someone – it was always a pleasant surprise a week or month or year after the meeting.

CC: Let’s be real, it’s demotivating when I’m not getting responses…it’s a bummer when I’m not shooting, period. (Hence the importance of personal work) It’s disappointing when I don’t win the job after I spent my weekend working on a treatment. The reality is that someone is going to get the job and it’s not always going to be me/you. The way I see it is – I’m trying to get in touch with the people who love my work and want to work with me. If I didn’t get the job it doesn’t mean my work sucks, it just means that the client found someone who is a better fit for the job (for whatever reason) and the ultimate goal for the agency/client is to find the person who is going to help them make the images they need (after all, they’re trying to do their job, they’re not trying to go around bruising egos, I hope). Trust that they made the right decision for the sake of the project. I keep in touch with whoever rejected me because there might be another opportunity in the future where I am a better fit. I respond with an “aww man!”, I accept that decision and move on. I accept that rejection is a part of the business (and life in general) and I eventually become desensitized lol. jk. sort of. Also, don’t confuse a lack of response with rejection, not everyone has the time to respond to every e-mail they receive, like Emiliano said, nobody owes you anything.

JS: In the past few years, I’ve learned how to separate out the emotion that gets attached to rejection in order to learn from the process. There is typically a lot of good information that you can absorb from that experience. Use this information to keep moving forward on your path.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Figure out who you want to be. NOT who THEY want you to be. Stay on that trajectory, no matter what.

JS: Be yourself. Be dedicated to the craft of making images for the love- the “money” will show up later. Follow your interests and make work about people and issues that you are connected to. Don’t compare yourself or your work to others. It is more than okay to make mistakes, they are the hands that we hold to get us back on track. Let Roxette be your guide.

CC: Make the work you want to make, show it (perfection is the enemy of progress). Repeat. Be patient. Find a community for support and to support. Figure out your business systems and data backup.

Link to this anwser.

JS: The nice thing about mistakes is that yield information so it’s really a good opportunity to learn something. With that said, I made a lot of mistakes earlier on…lol

One in particular, at the early stage of my career, I was in a rush to meet with editors to show them that I “existed.” The meetings that I had set up really didn’t have a purpose other than “oh hey, look at my work and please hire me” so the conversations weren’t that deep. I noticed that the meetings ended up being pretty short because I wasn’t able to offer anything substantial. Now, I am more intentional in terms of who I am contacting for meetings and I make sure that there is a clear reason for me to show up at the office. I’m either coming in with a project proposal or presentation. Also, making sure the work that I’m going to share is ready to be seen by the world.

EG: I’ve accepted several jobs over the years that I probably should have passed on. Earlier in my career, getting a call felt like a victory, so I said yes to any job that I was asked to do. In retrospect, it probably wasn’t worth the few hundred bucks. Nowadays, I’m more conscious of what I say yes to. We all have a finite amount of energy, and sinking that energy into projects that don’t fulfill you is a great way to burn yourself out.

CC: Same as Emiliano, I wasn’t comfortable with saying no. I was just excited that someone was willing to pay me to make photographs. While I had to make a living, I wonder if I had instead spent time on personal projects if I’d be more strongly aligned with the exact type of projects I wanted to work on sooner. Secondly, something I had to learn from and still make the mistake from time to time is not being hyper-specific about the scope of a job so that the client and I are on the same page. For example, creating a deliverables timeline is so that if they ask for something earlier then you can remind them that you agreed upon X date so any earlier would require a rush fee. If you agreed on 10 images then each additional image will cost $XX. Same with usage, retouching, etc. The more specific you can be, the better you protect your time and energy.