A Professional Photographic Knowledge Base

↓

Fuck Gatekeeping is our attempt to open our personal “gates” and provide the learnings, successes and failures we’ve experienced as professional photographers for the benefit of underrepresented communities.

EG: Figure out who you want to be. NOT who THEY want you to be. Stay on that trajectory, no matter what.

JS: Be yourself. Be dedicated to the craft of making images for the love- the “money” will show up later. Follow your interests and make work about people and issues that you are connected to. Don’t compare yourself or your work to others. It is more than okay to make mistakes, they are the hands that we hold to get us back on track. Let Roxette be your guide.

CC: Make the work you want to make, show it (perfection is the enemy of progress). Repeat. Be patient. Find a community for support and to support. Figure out your business systems and data backup.

Link to this anwser.

JS: I spend more time than I would like to admit in front of computer- sending emails, retouching work, updating my website, biz dev, YouTube rabbit holes, making calls, sitting on Zooms, PrePro, blessing recipients with PDFs, invoices and WeTransfer links. If I have an assignment coming up, the preparation starts a couple days before- getting lighting concepts dialed in, ideas for locations and concepts plus moods as well as color palette. The day of a session, my only focus is making photographs, being present and enjoying the time. If I’m dipping out for a 10 day personal work trip, then my out of office reply is on so that I can concentrate on making the most of my time developing the project. The big change for my career was when I started using a calendar and understanding the need to be more thoughtful with my time- this took a while for me to figure out…

CC: Similar to Jared, I spend a lot of my time in admin world. My weeks look different depending on current project timelines and upcoming shoots. This can mean I’m scouting, pulling references, and producing one day, picking up equipment and shooting the next, in post/retouching/billing the next, or I can be spending one or two days creating a treatment for an upcoming bid. I still do most things I did at the beginning of my career now besides estimating, negotiating. My agent also helps a lot with marketing and outreach. When I first started out, I didn’t have any boundaries between work and my personal life – I felt as though every waking hour not invested in furthering my career was a lost opportunity. I realized that wasn’t healthy nor true. I find that my task list is never-ending but what’s changed as my career has evolved, is the balance between work and rest to avoid burnout and prioritizing the important but not externally urgent tasks (personal work) that are investments in my portfolio, alongside the urgent and important tasks (client work) and letting the rest fall by the wayside.

EG: Every day is very different. Some days it’s building a creative deck all day. Others it’s just sitting around and trying to focus on invoicing and other office stuff. Some days I blow everything off and play tennis. And then on production days it can be full gas all day and night. The more rigor you can bring to your day-to-day practices, the better. I’m not great at discipline and rigor . . . so I try to make up for it by really focusing when I actually sit down to do something. It’s not atypical for me to stay up until 3 or 4 in the morning just trying to build my network, researching, or blowing out some ideas.

Link to this anwser.

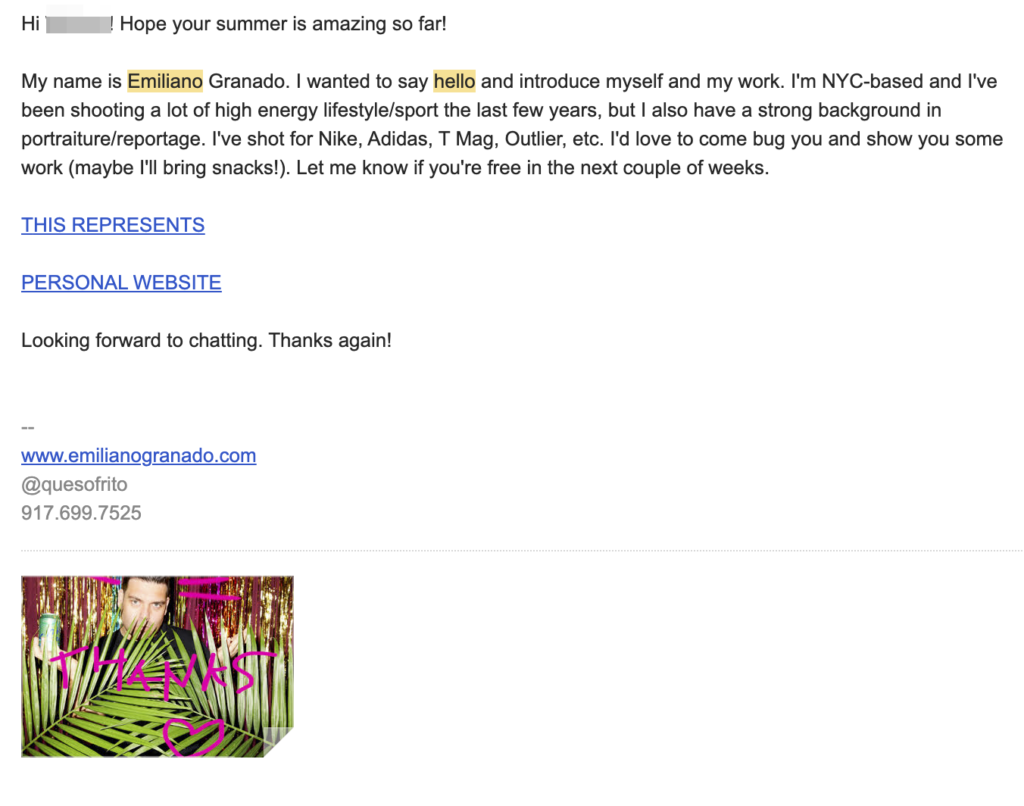

EG: I always think that whether you can figure out how to start assisting is essentially a litmus test of whether you’re gonna make it or not. The formula is pretty easy, tbh.

1. Find photographers you like.

2. Email them. Say hello. Tell them you like their work and you’d love to assist someday.

3. Don’t expect a response. If you get one, great.

4. Stay in touch a few times a year.

5. Repeat until you no longer want to assist.

There it is. That’s the secret to a career in photography. Research. Interact. Repeat. This works for assisting, for magazines, for commercial clients, etc etc. If you’re cool, or talented, or a hard worker, or really pleasant, or any combination of those, you’ll be fine if you follow this formula.

JS: An easy way to get started is to assist your friends, you will both learn quite a bit in the process and it’ll be low pressure since you know each other. Another way is to reach out to photographers in your area. Send them a polite email sharing your background and experience level along with a link to your website, conveying your interest in assisting. Join a professional organization such as ASMP or APA both have databases for assistants.

CC: Do what is suggested above and follow up. I started assisting by doing 1, 2, and 3. I’ll also add that I didn’t get any responses from the 30+ emails I sent and when I followed up with all of them I received a response from 2 people who I ended up assisting regularly for two years and learned a ton from (while also testing and assisting my friends – make friends with other photographers at your level at local photo events and you’ll level up together as time goes on). As Emiliano said, it’s important to stay top of mind and if a photographer’s usual assistant isn’t available and you happen to follow up on your email, you might get hired. The tricky part is not having all the experience necessary (or any experience) to be a first assistant so Jake Stangel created this super helpful video. I’d have to say that nothing compares to being able to play with all the gear IRL so I would also suggest reaching out to 1st assistants and asking if you can be brought on as a 2nd or 3rd assistant on bigger jobs. I learned so much this way – during downtime, the 1st assistant would show me how all the gear worked. You can also try to get into the equipment rooms at studios or rental houses to familiarize yourself with the gear and meet photographers that way.

Link to this anwser.

EG: You have to approach this as a long-term thing. Just because a photo editor followed you on Instagram doesn’t mean you’re going to get a job. Just because they responded to your email doesn’t mean you’re going to shoot the cover. You’ll literally send hundreds of messages before getting your first jobs. You’re going to bid dozens of jobs and not get any of them. You’re going to spend many days writing treatments that you won’t win. You’re going to strike out a million times before you get any jobs. No one owes you a damn thing. It’s a slow, slow process, so bunker down for the long haul. The only thing that you can control is your creative output. Make sure it’s 🔥🔥🔥.

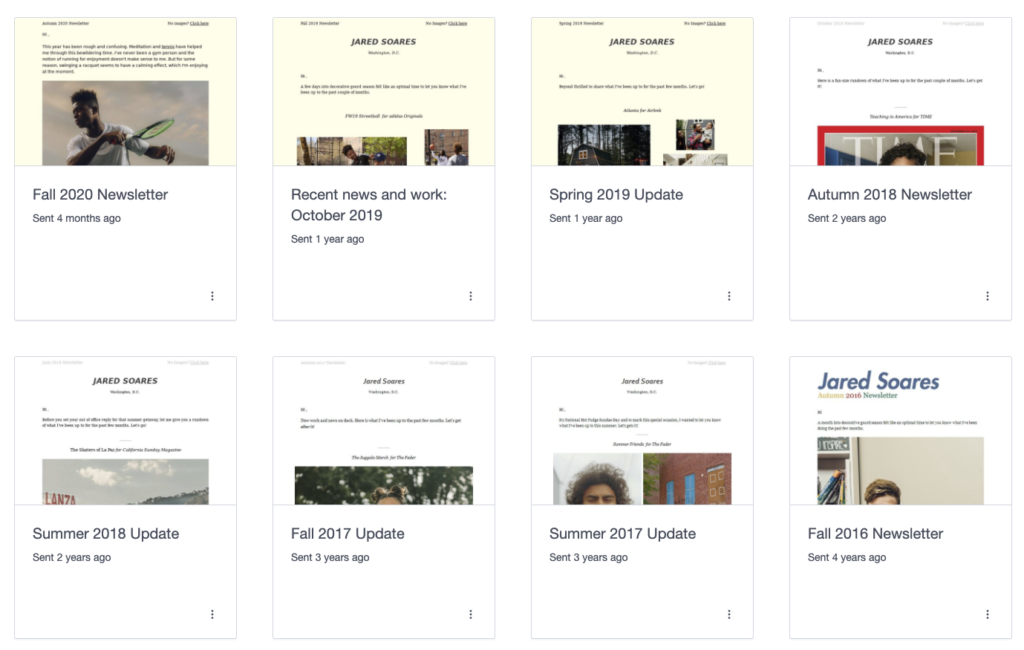

Some basic math: I may send out a newsletter to, say, 1000 people. Of those 1000 people, only about 100 of them will read it. Of those 100, only 25ish will respond with “great work!” And only about 1 or 2 of them will eventually hire me at some point. Maybe next month, but probably next year. The turnaround on success and ROI on any marketing is measured in years . . .not months and definitely not days. I’ve never walked out of a meeting knowing I was going to get a job from someone – it was always a pleasant surprise a week or month or year after the meeting.

CC: Let’s be real, it’s demotivating when I’m not getting responses…it’s a bummer when I’m not shooting, period. (Hence the importance of personal work) It’s disappointing when I don’t win the job after I spent my weekend working on a treatment. The reality is that someone is going to get the job and it’s not always going to be me/you. The way I see it is – I’m trying to get in touch with the people who love my work and want to work with me. If I didn’t get the job it doesn’t mean my work sucks, it just means that the client found someone who is a better fit for the job (for whatever reason) and the ultimate goal for the agency/client is to find the person who is going to help them make the images they need (after all, they’re trying to do their job, they’re not trying to go around bruising egos, I hope). Trust that they made the right decision for the sake of the project. I keep in touch with whoever rejected me because there might be another opportunity in the future where I am a better fit. I respond with an “aww man!”, I accept that decision and move on. I accept that rejection is a part of the business (and life in general) and I eventually become desensitized lol. jk. sort of. Also, don’t confuse a lack of response with rejection, not everyone has the time to respond to every e-mail they receive, like Emiliano said, nobody owes you anything.

JS: In the past few years, I’ve learned how to separate out the emotion that gets attached to rejection in order to learn from the process. There is typically a lot of good information that you can absorb from that experience. Use this information to keep moving forward on your path.

Link to this anwser.

EG: First, let’s identify why I, personally, would want to shoot film on a job. For me, the combination of the cameras, the lenses, and the film ‘look’ create a certain picture quality that I still can’t really replicate with digital cameras. Also, I tend to shoot almost exclusively medium format film. Those cameras are slow and clumsy, so they force me to go into a mental zone that is hyper focused, methodical and way more intentional. I really enjoy that space and feel like the images are better, afterwards. Whether that’s true or not is 100% subjective, but that’s just how I feel. So if a job feels like it could yield some especially powerful imagery, I will try to shoot film if the logistics allow for it.

Everyone will have their own reasons for wanting to shoot film, and it’s important you identify why you’re even complicating things for yourself!

Once you identify that you’d like to shoot film for a certain project, now it’s time to get that approved by the client. Some clients will love the idea and embrace the added complications. For some clients/jobs, the answer will be ‘absolutely not.’ And maybe some jobs will allow for a hybrid shoot with some shots on film, but most on digital, or something like that. Every job will be different.

In order to get approval, you’ll most likely need to let the client know how much it costs and how much longer it will take to see images. This is really as straightforward as estimating how many rolls you will shoot, what that costs to buy/develop/print/scan and put that into an estimate. On bigger jobs, you may be able to add a little on top of those costs to cover the time to buy, run to lab, etc etc. Something like a 20% markup on top of the actual costs. For example, one roll of Kodak Portra 400 costs $10 to buy and $20 to develop and scan (medium res). If I anticipate shooting 10 rolls on a job, then it’s $30 x 10. You may need to add a high res scan on top of that or an actual c-print if that’s your process.

An example from an actual estimate below:

Example shows a 2-day shoot where I would rent two cameras and shoot an estimated 20 rolls of 120 per day @ $35/roll

Obviously, on a bigger shoot an added cost of $1900 is not that much. But for smaller shoots, it may be problematic.

Link to this anwser.

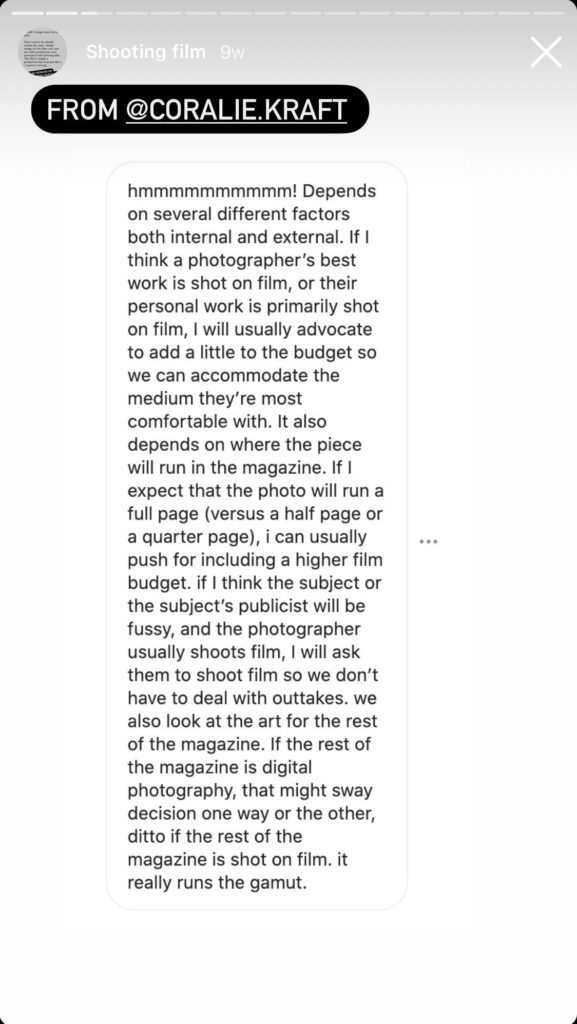

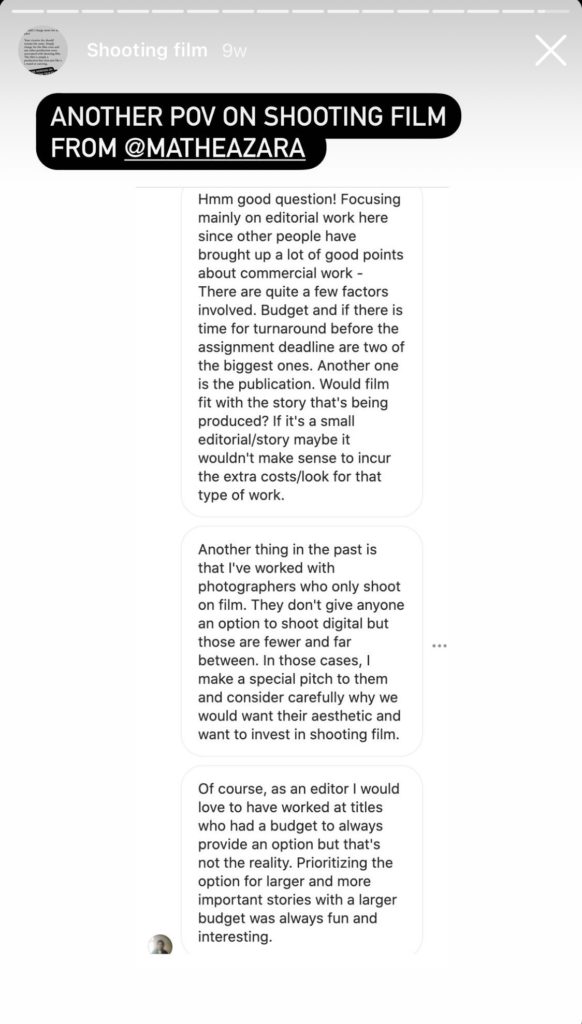

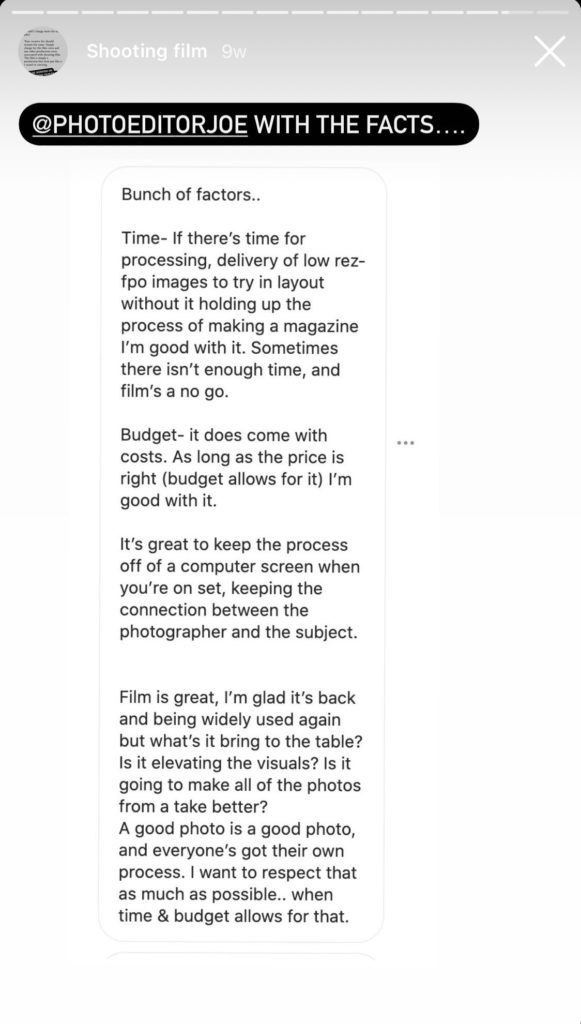

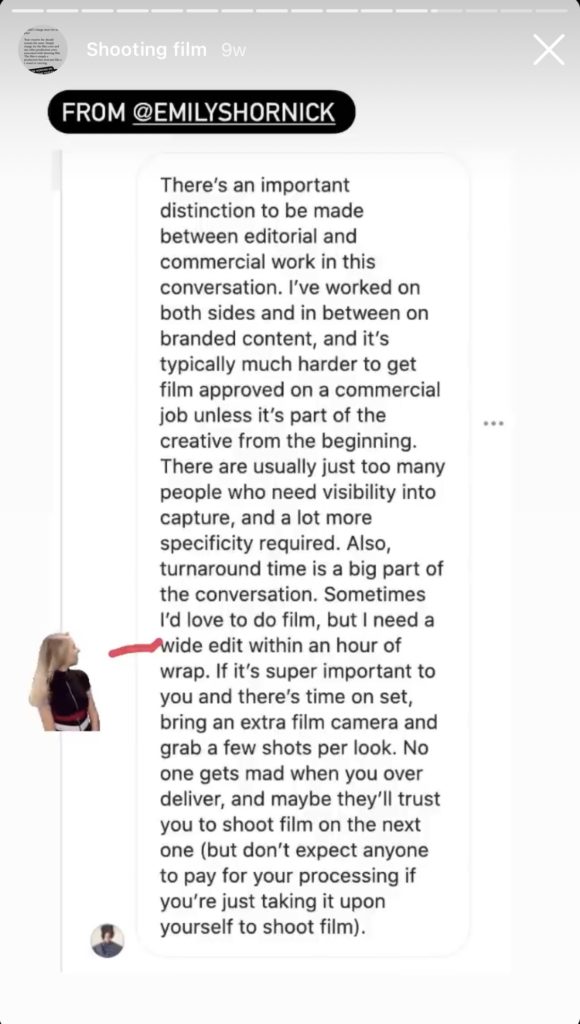

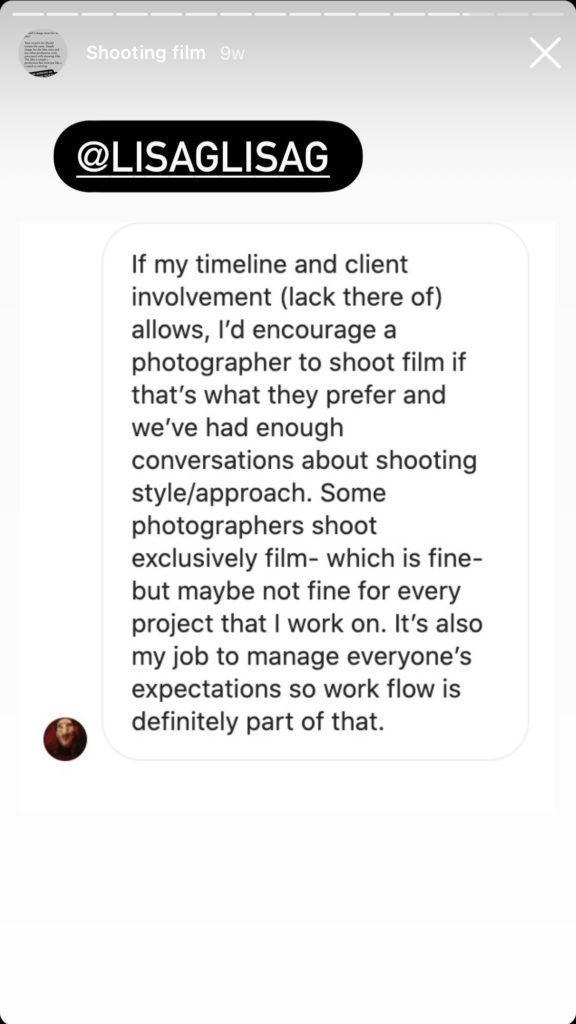

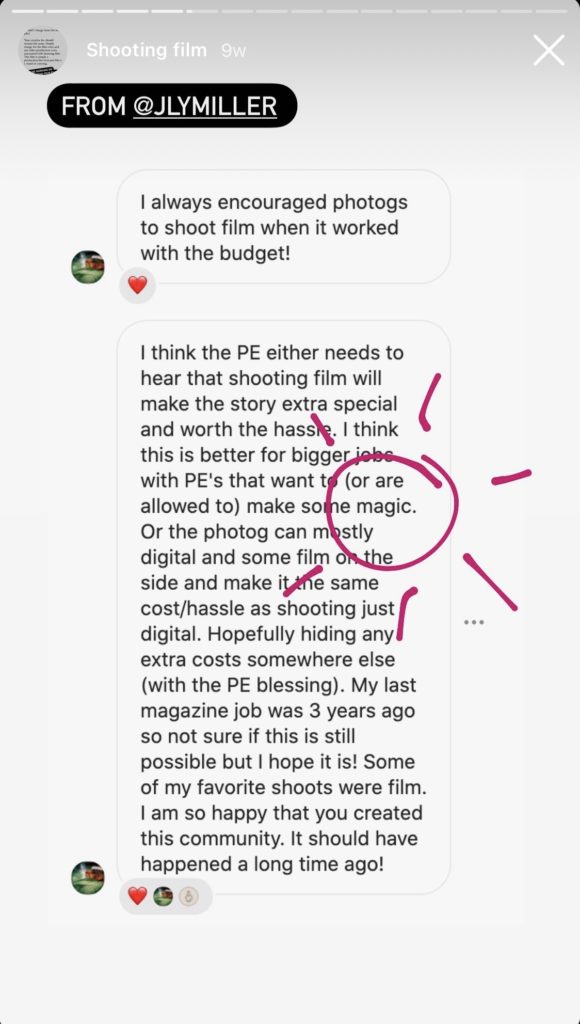

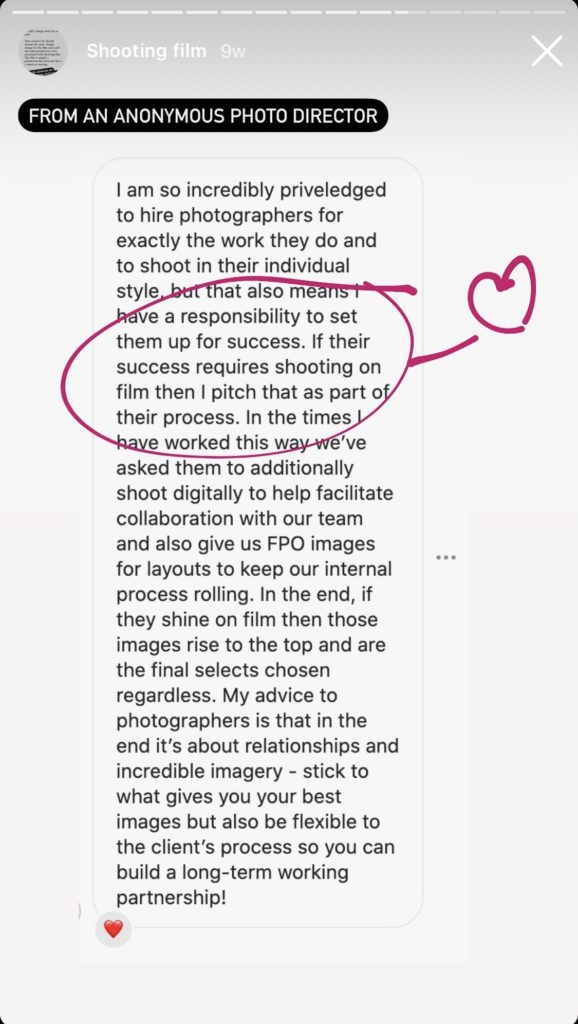

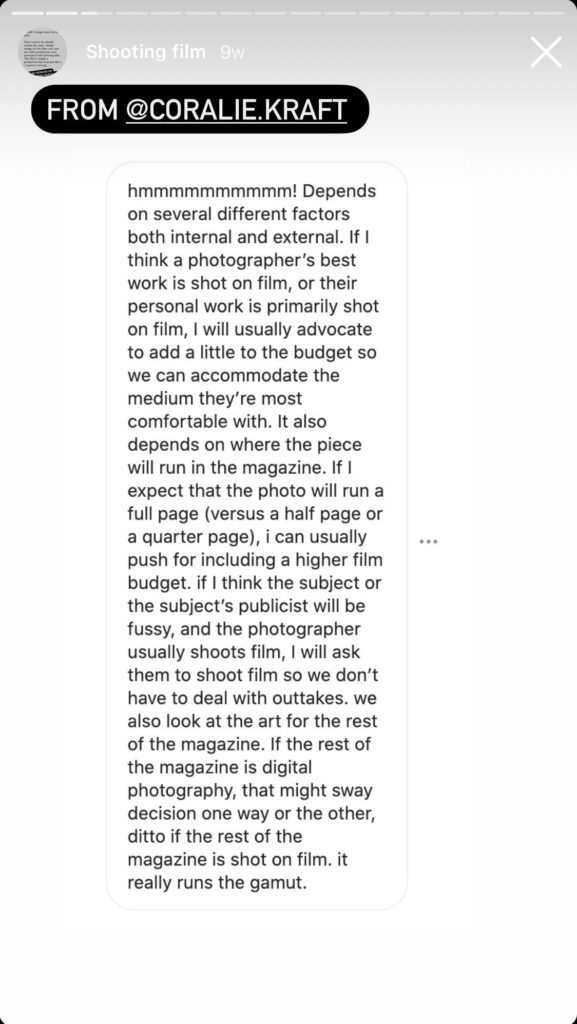

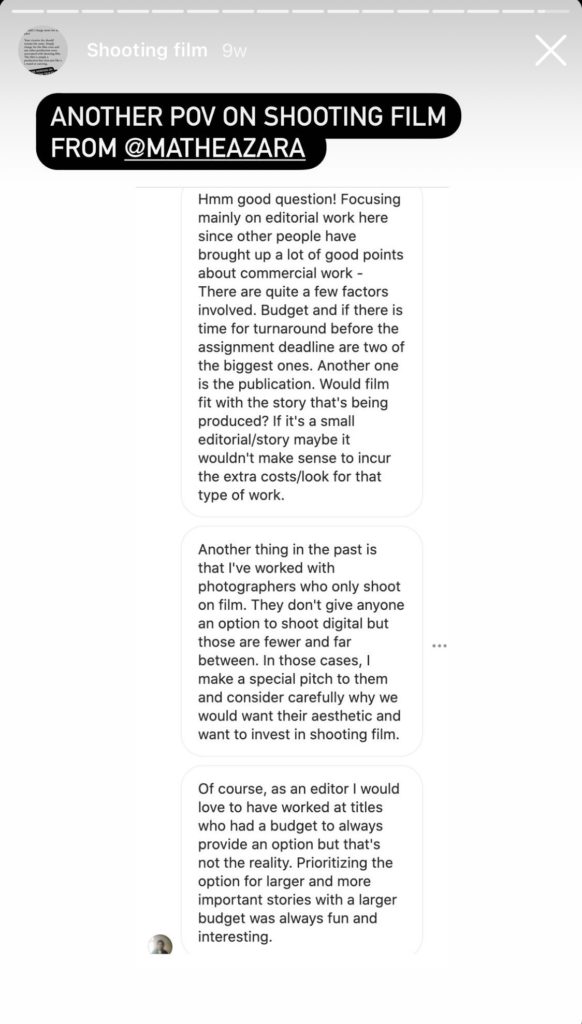

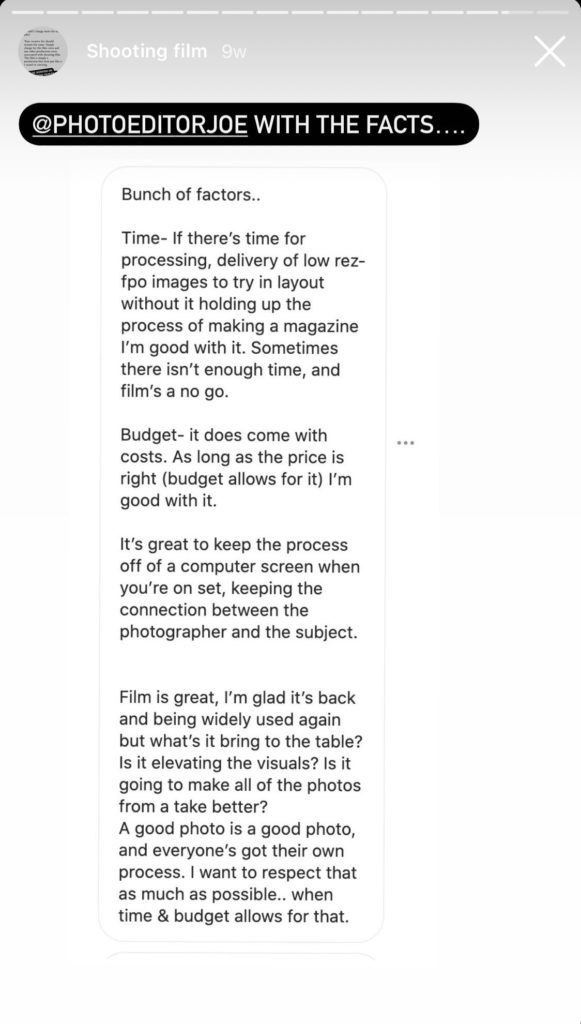

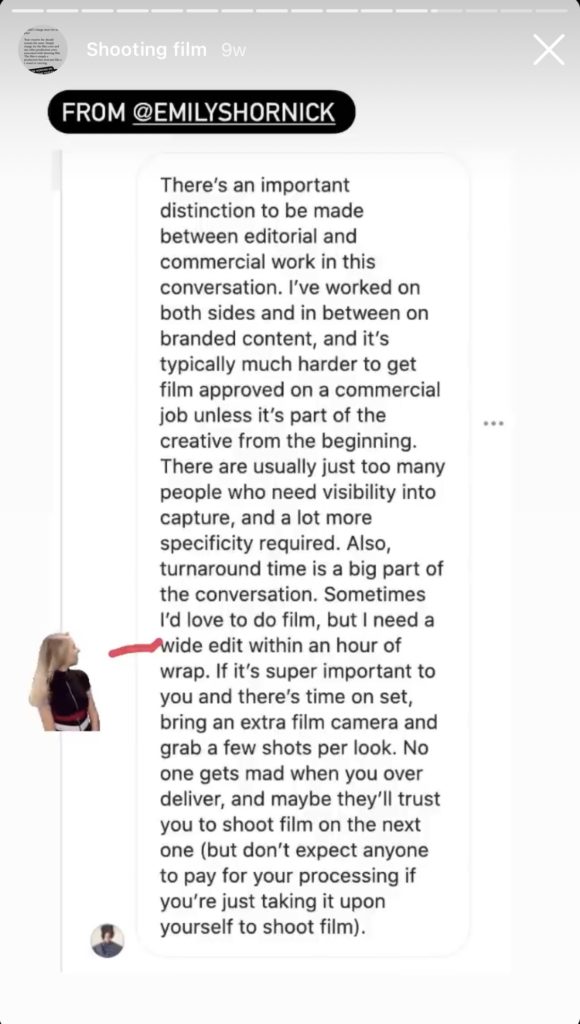

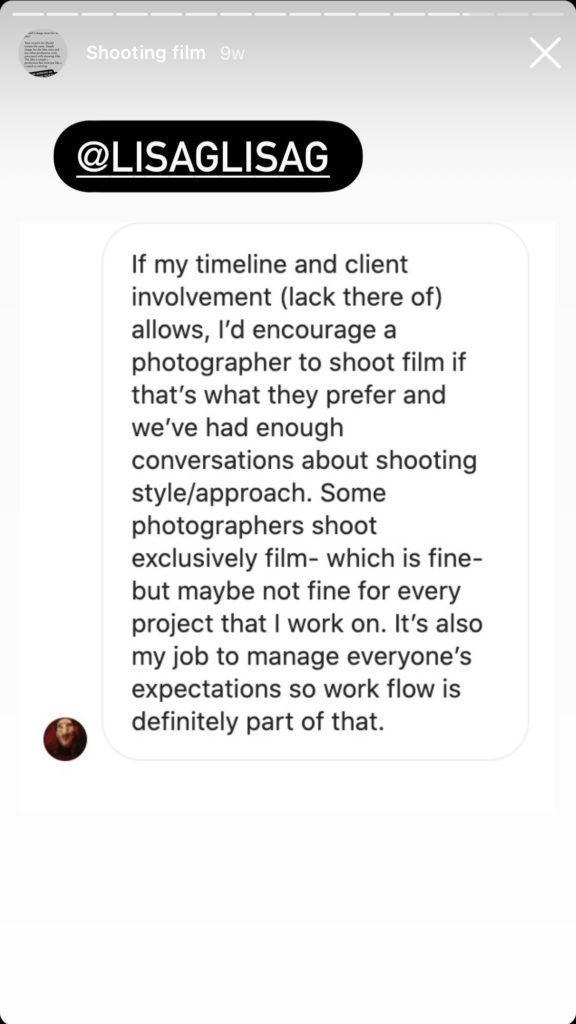

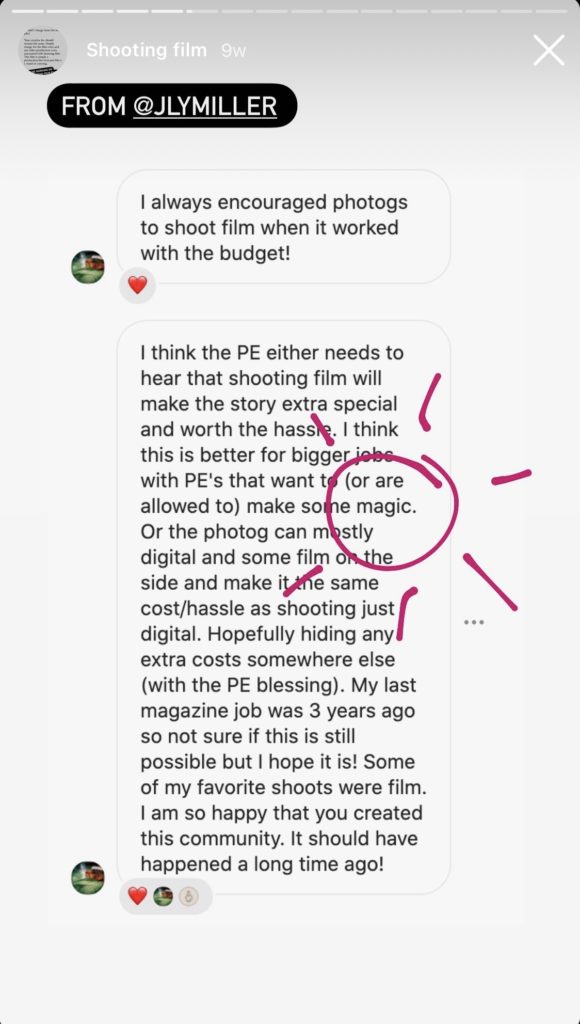

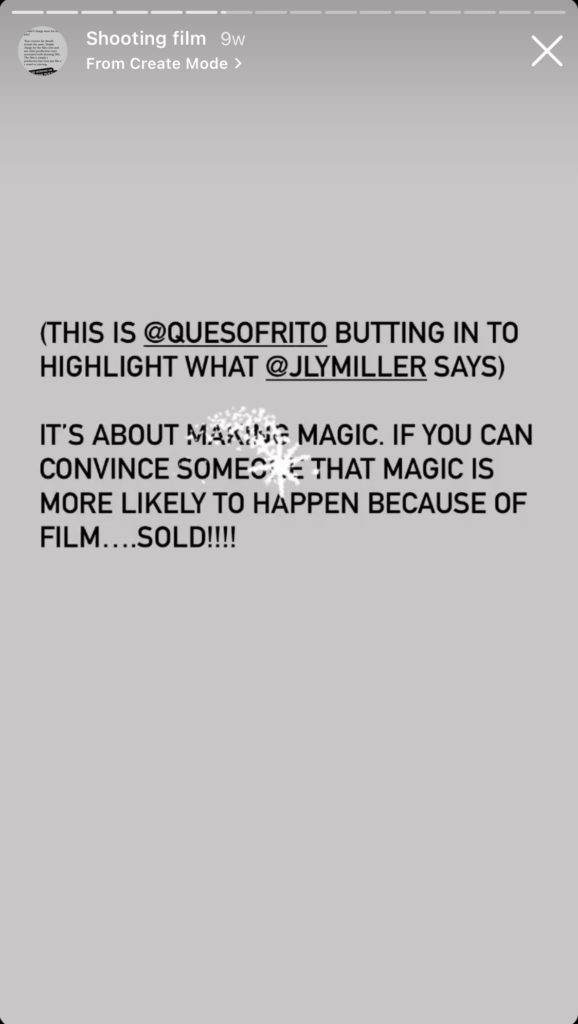

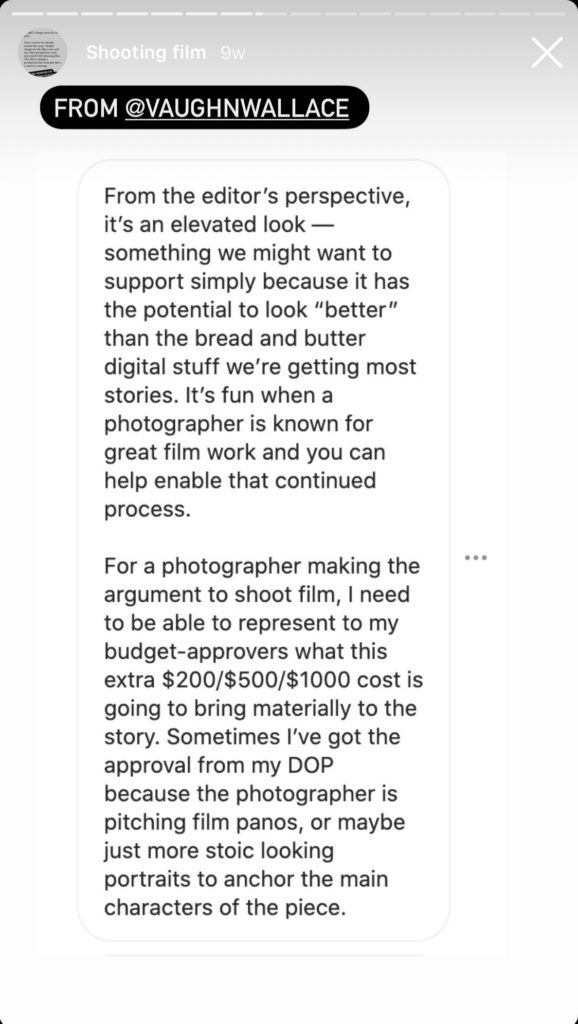

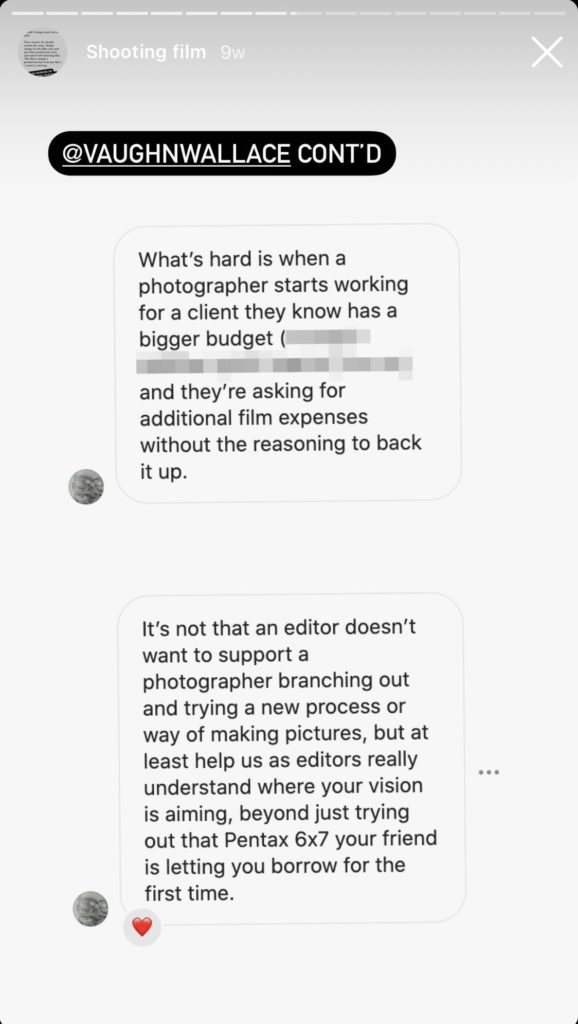

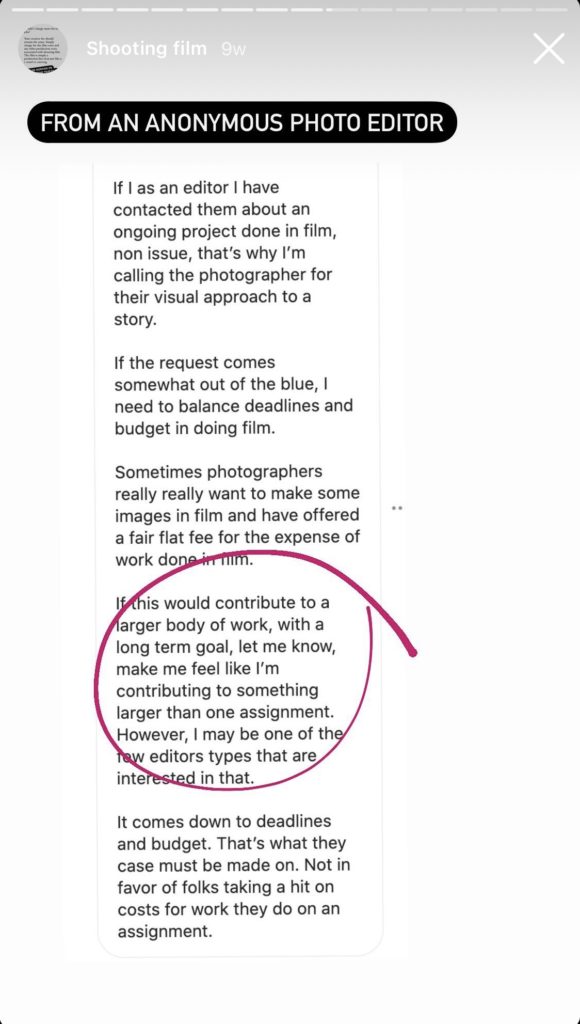

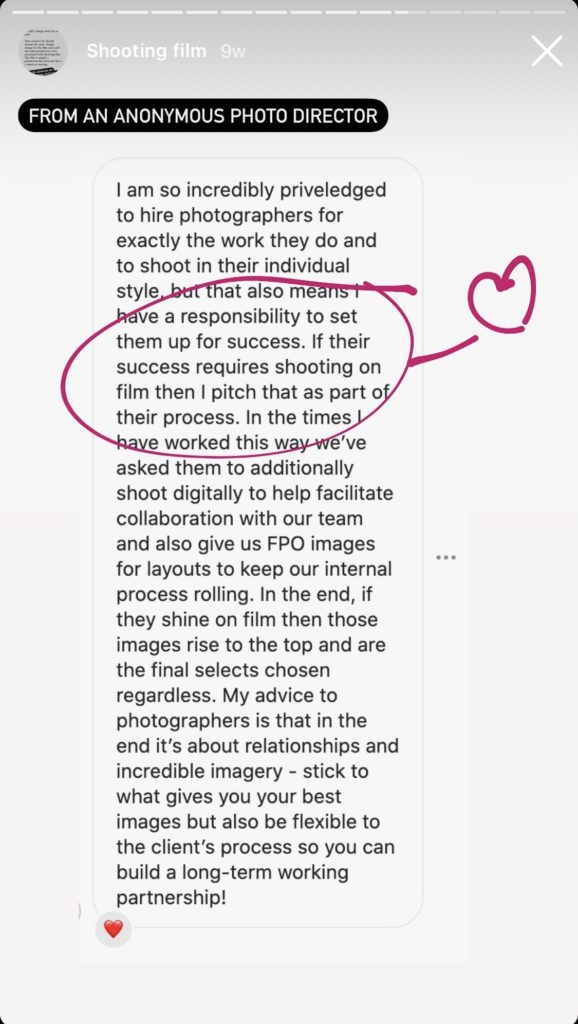

We polled the public on our IG and here are answers from the editors themselves!

EG: Make the type of work you want to be hired to make.

CC: Agreeing with Emiliano here. Think of it from the client’s perspective – they’re making an investment in your eye, your images, and your ability to run your set and deliver on the brief. What is in your portfolio demonstrates what you’re capable of, so you’ll get hired for what you show. It’s the same reason I look at photos on yelp 🤤

JS: This is an evidence based industry, in order to get the work you want, you have to demonstrate that you are able to do it- consistently.

Link to this anwser.

EG: For sure. I personally don’t like to mix too much because my brain gets confused, but if you can identify scenarios that you like for digital and others for film or just shoot a mix at all times, then go for it. I’ve definitely shot mostly digital before and when a situation is really hitting hard, then I grab the film camera. I’ve also brought my digital camera to use as a polaroid. Adjust. And then move to the film cameras. I’ve shot A LOT of film in my life, so I’m pretty confident in my cameras and my ability, but it’s ultimately about shooting a ton and believing in yourself!

Link to this anwser.

JS: The nice thing about mistakes is that yield information so it’s really a good opportunity to learn something. With that said, I made a lot of mistakes earlier on…lol

One in particular, at the early stage of my career, I was in a rush to meet with editors to show them that I “existed.” The meetings that I had set up really didn’t have a purpose other than “oh hey, look at my work and please hire me” so the conversations weren’t that deep. I noticed that the meetings ended up being pretty short because I wasn’t able to offer anything substantial. Now, I am more intentional in terms of who I am contacting for meetings and I make sure that there is a clear reason for me to show up at the office. I’m either coming in with a project proposal or presentation. Also, making sure the work that I’m going to share is ready to be seen by the world.

EG: I’ve accepted several jobs over the years that I probably should have passed on. Earlier in my career, getting a call felt like a victory, so I said yes to any job that I was asked to do. In retrospect, it probably wasn’t worth the few hundred bucks. Nowadays, I’m more conscious of what I say yes to. We all have a finite amount of energy, and sinking that energy into projects that don’t fulfill you is a great way to burn yourself out.

CC: Same as Emiliano, I wasn’t comfortable with saying no. I was just excited that someone was willing to pay me to make photographs. While I had to make a living, I wonder if I had instead spent time on personal projects if I’d be more strongly aligned with the exact type of projects I wanted to work on sooner. Secondly, something I had to learn from and still make the mistake from time to time is not being hyper-specific about the scope of a job so that the client and I are on the same page. For example, creating a deliverables timeline is so that if they ask for something earlier then you can remind them that you agreed upon X date so any earlier would require a rush fee. If you agreed on 10 images then each additional image will cost $XX. Same with usage, retouching, etc. The more specific you can be, the better you protect your time and energy.

JS: My biz is structured as an LLC. Always best to keep personal and business assets separate plus it helps with taxes too. Talk to an accountant to figure out what makes sense for you.

CC: I incorporated my business after being a sole proprietor for 8 years for tax benefit and liability reasons. I was fine with not incorporating before because I didn’t have any personal assets that I was concerned about losing should something go wrong and I get sued. My business is currently incorporated as an LLC and treated as an S-Corp (confusing, I know). Based on my income, the tax benefits I receive outweigh the annual fees associated with filing as an S-Corp. Everyone’s tax situation and income is different so it might not make sense for you to change your business structure. If you want to learn more read this and reach out to a CPA or accountant. If you’re looking for one in the LA area, I work with Jason at Safer & Co.

Link to this anwser.

EG: My process is pretty straightforward. I drop off film at the lab and they give me pretty big scans of the entire shoot in about 3 days. That goes into the computer and its just like a digital shoot at that point. If the client needs a bigger file, then I may do additional high res scans of the final files.

You have to communicate what this will look like to the client. I live in NYC, so I can run to the lab pretty much the same day and in 2-3 days have decent scans ready to go. But your location or post processing process may differ. I find that 2-3 days is not really a deal breaker for most situations.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Don’t. If you can avoid it.

Obviously, sometimes you gotta take the money or the project is something you really want to do. Try to negotiate and ask if there’s any flexibility on the terms or the budget.

JS: Contracts are always negotiable. Do the best to communicate that the terms are uncomfortable and overreaching, then propose a new set that are more favorable to you. Also, it’s more than okay to walk away.

CC: Sometimes clients want a buyout of images or WFH so they don’t have to deal with licensing. There’s an opportunity to ask how the images will really be used and negotiate to keep the copyright and discuss licensing. You get to decide whether it’s worth losing out on any opportunity for a license extension in the future or to license the body of work to a third party in the future. Some great advice here from Photo Bill of Rights.

Link to this anwser.

EG: I can think of two really specific successes. Many years ago, I found a cool new agency somewhere on the Internet. They had just started out and were doing some cool small projects. I found their address and sent them a postcard with a funny message. They really liked it and posted it on their blog. I eventually met them in person to say hi. We stayed friendly for years, and last year they asked me to shoot a really great project for a big athletic brand.

Back in 2008, I published a newsprint publication called “Thank God That’s Over.” It was a humorous photo essay taken on a five-day cruise from New Jersey to Bermuda. It was every bit as awful as you can imagine. To this day, people still reference that newsprint thing. I learned that to make good photos is not enough. You have to package them up nicely and deliver it to the world in a format they will enjoy.

JS: This past Fall, I sent an email newsletter to a list made up of mostly photo editors in order to share some recent editorial work. A photo director from a magazine replied and inquired if I was available and interested in working on an assignment later that month.

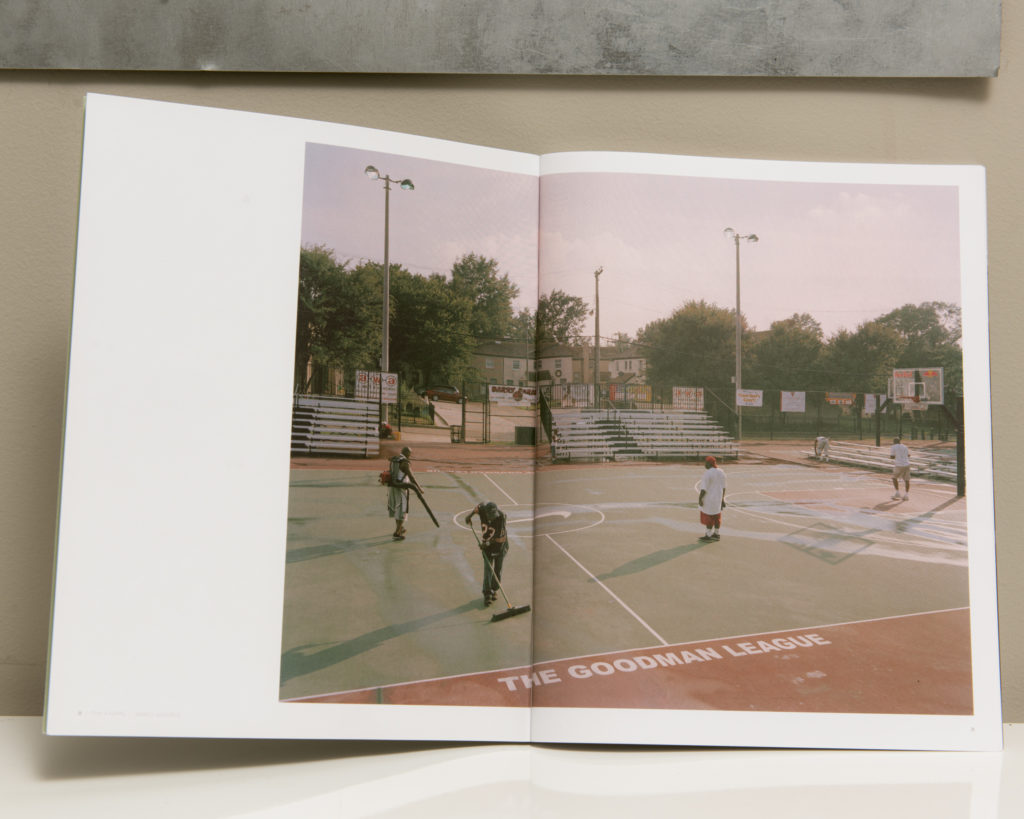

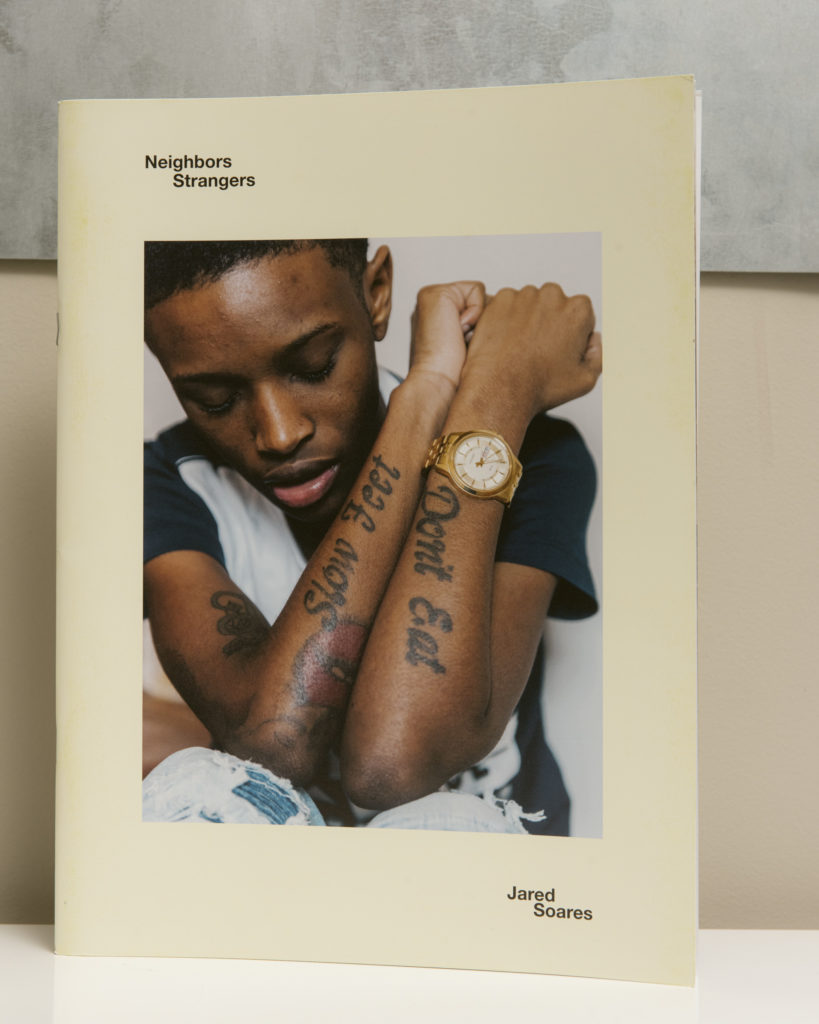

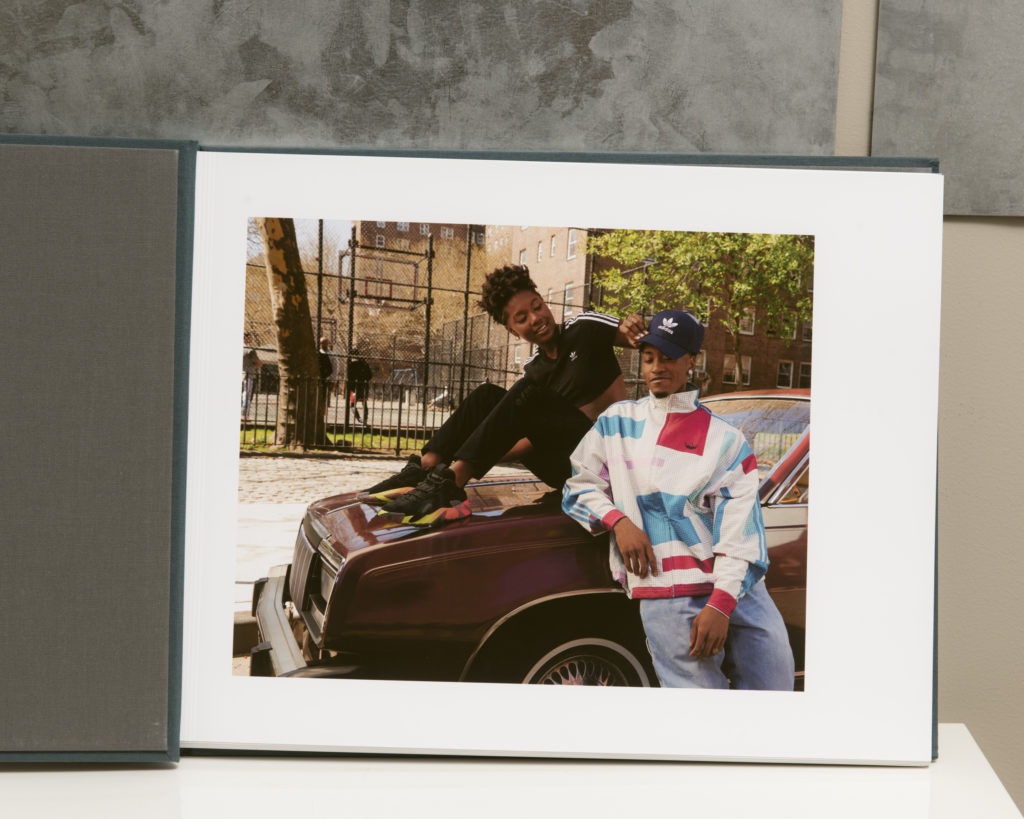

A couple years ago, I made a booklet to accompany a personal project about a summer basketball league. Unsure of how it happened but the booklet wound up on the desk of an individual who works for a popular sportswear brand. This person ended up hiring me for some of my early commercial work at the brand and later connected me to a creative agency that I still work with today.

CC: I signed with my agent as a result of my “marketing” efforts – they saw my work in a magazine, then they received my email newsletter, after they received my printed promo they invited me in for a meeting.

A client received the same printed promo and held onto it for nine months before the right job came along – a two day ad job.

I cold emailed a handful of editors at the NY Times introducing myself and my work and within 2 months I was hired by two different editors to contribute portraits.

I will also say that the marketing efforts are compounding like it was with my agent and it’s a matter of timing – when the right project comes along and the client remembers your work or happens to see it (somewhere – newsletter, promo, magazine, email) and they’re looking for someone to hire that has your style. Keep at it!

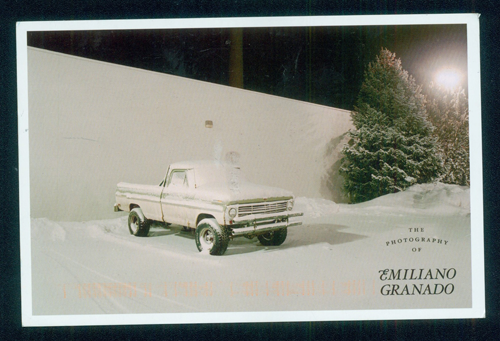

EG: The standard is a website plus an IG presence. BUT. If your work really can benefit from some non standard presentation, then by all means.

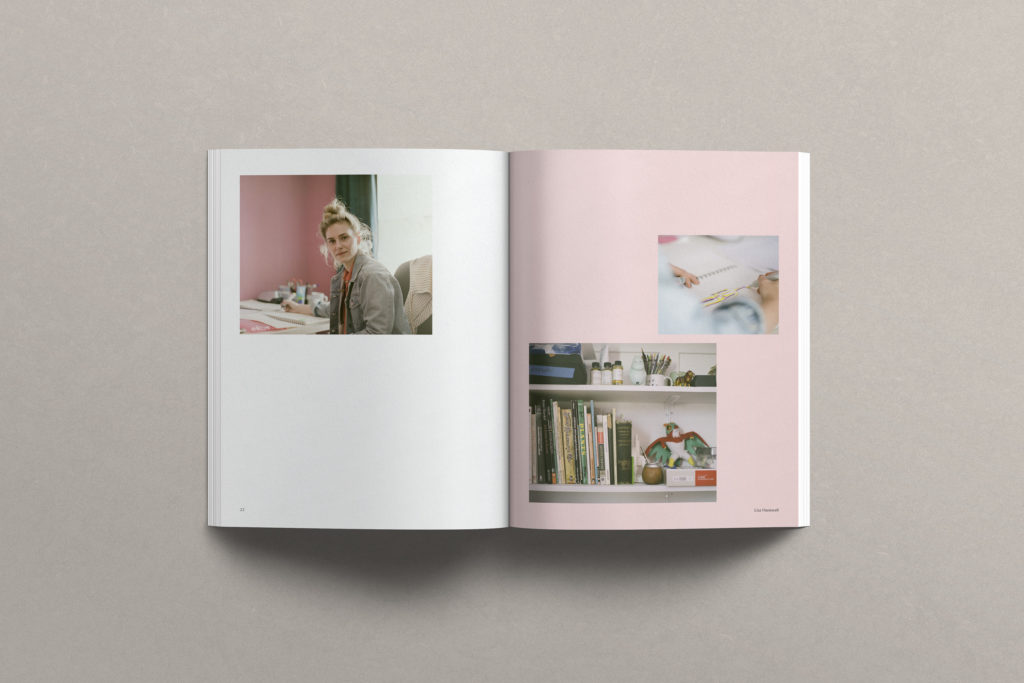

For in person meetings, almost everyone has a portfolio (of varying price points) or a tidy digital presentation (ie iPad). It doesn’t need to be a custom $400 portfolio either! As long as you show that your photos are technically sound and you’re capable of building cohesive bodies of work, no one really cares if the portfolio itself cost $50 or $500. Also, I know several photographers that would come to meetings with a box of prints. If that feels better for your work, then go for it. But please remember if your presentation is too kooky, then you’re taking attention away from your photos. For reference, this is my current portfolio.

For online presence, a website is essentially a must. I’ve seen people get hired from tumblr pages and other alternative forms, but that was before website got really easy to construct. The current version is people with only an IG presence and no website. The people that can pull that off are prolific and very talented. They are the exception to the rules.

Another quick note about websites. Display your best work only. I think most people would rather see only 5 great images than 5 great images among 20 mediocre ones. This is painfully common. No one wants to see some e-comm photos of bags just because you think it shows you’re a “commercial photographer!”

JS: Short answer: YES. A dedicated website to display your photography the way that you want to is crucial. Additionally, this space on the web will be what people in hiring positions use to reference your work. Pre-Pandemic, I would have highlighted the value of a physical portfolio but since we’re still living in amidst Covid, I don’t think it is necessary because in-person meetings are not taking place. Another approach would be to make a PDF portfolio that could be shared directly with an editor or art buyer.

CC: I think you need a website because it’s a different way to experience and present your work than IG and likely the best format for your work to be seen (thinking of landscape images across three carousel posts on IG). The way you design your site can also tell people more about you and your style. The same goes for your printed portfolio for in-person experiences.

Also, this note was submitted to our site –

Link to this anwser.I beg of you to please tell photographers to put their contact information on their websites. Phone number and email. Get a google voice number if you don’t want your info out there.

But I beg of you, HELP ME HIRE YOU. PUT AN EMAIL AND PHONE NUMBER ON YOUR SITE.

AND TELL ME WHERE YOU ARE.

CC: Having an agent is the key to booking jobs. At least that’s what I thought when I was starting out. Instead of looking for jobs, I was looking for an agent. The question to ask yourself first is, do you need an agent? Do you have the portfolio and the commercial experience that an agent can confidently get behind? Are you working so much that you’re missing out on opportunities while you’re on set?

You can absolutely get commercial work without being represented. You’ll need to learn how to negotiate and put together bids. Having an agent doesn’t guarantee you’ll be getting jobs – it really depends on how hard your agent works, their reputation and network, and how hard you’re working to facilitate what they do and what you’re doing (personal work, newsletters, promos) in tandem with their efforts.

Also, photographers pay their agents a commission (typically 20-30%) whether or not the job came through the agent. The only exception to this is if the client is on a pre-existing house client list that your agent approves prior to you signing. My agent solely focuses on commercial opportunities so I am still doing my own marketing for editorial work. If you are at the stage in your career where you can manage doing what an agent does on your own or paying a consultant to help for an hourly rate rather than a % of your fee, does it make sense for you to have an agent? If it does, then go ahead and start sharing your work with agents and build relationships with them the same way you would with a client. Get to know them and work on a few jobs together to see if they’re a good fit. They become a big part of your brand. Listen to this podcast starting at the 27min mark to get a better idea about the thought process from an agent’s perspective.

JS: Photography is all about relationships and this applies to working with agents too. I realized that I needed the help of an agent when I noticed that commercial agreements were beyond knowledge of contracts and that the negotiation process required a significant time investment. Additionally, I was starting to get busier with both commercial and editorial work along with maintaining my personal practice as an artist. My thought process was that I needed to find an agent who could take the business side off my plate so that I could focus more on the creative. The way that I started the search was to reverse engineer it, I was interested in seeking out agents that had preexisting relationships with brands and ad agencies that I had already worked with or desired to collaborate with in the future. So I did the breadcrumb trail thing and paid attention to who photographers were tagging in their social posts. Also, spoke to a few photographers who had been represented and got their takes. I made a list and contacted a few to introduce myself and then followed up when I had jobs that made sense to bring an agent onboard. Working with an agent on a nonexclusive basis is a good way to get to know them and how you both work together. This process is a lot like dating, it’s slow and it should be.

And here is a pretty extensive list of photography agents by APhotoEditor, here.

EG: The short answer is, if you have to ask, you’re not really ready for an agent.

The longer answer involves lots of hard work, establishing yourself as a name, tons of introductory emails, networking, meetings, successful projects, a good reputation, some positive energy behind you, etc etc. Carmen and Jared hit up most of the points above. But tbh, if you don’t know how to research, network with and get the attention of agents, then you probably haven’t learned how to research, network with and get the attention of clients, yet. It’s essentially the same thing just with a different set of people.

Additionally, once you’re ready, agents will start to say hello and show up in your social media, etc. Of course you should be proactive in letting them know you exist, but their literal job is knowing whats hot. And if you’re hot, then they’ll find you.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Research! Who are your peers? Who has the career you want? Who hires them? Who do they follow? What clients will realistically hire you? Follow all of them and try to befriend them all. Don’t be annoying. If you do it right, you’ll start getting calls. It might take a few years, but keep doing it. HEAD DOWN. KEEP MOVING FORWARD.

JS: All of this info is at your fingertips these days- Google, Instagram, and LinkedIn (yeah I know it’s a bummer of a site but it’s pretty useful these days for figuring out where people are working). If you’re able to answer these questions “what’s your work about and who are you trying to reach” you will be able to put together a shortlist that you can follow on socials or reach out directly and politely to on IG.

CC: It was helpful for me when I sat down a made a shortlist, like Jared suggested, of the brands and publications I wanted to work with and why or specific categories of clients you want to work with. From there, look for art producers, art buyers, art directors, photo editors, photo directors, etc. The internet is your friend. It also doesn’t hurt to ask for introductions or referrals from existing contacts.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Being a photographer is like 25% taking photos and 75% building a network and letting people know you exist. If you’re not committed to that 75%, you’re not doing it right.

CC: I do this by actively sharing it with people or trying to get published in places where more people are looking. If I want new people to see my work, merely sharing it on your IG and website won’t suffice. As Emiliano said, the act of getting your work seen is active work. Who am I directly sending this work to who would appreciate it? Specific photo editors at places that publish this type of work? Specific art directors/buyers who have clients in this category? Art blogs?

Link to this anwser.

JS: I use a combo of Instagram, Google and Linkedin to figure out contacts and email address styles. Also, I trade contacts with friends and we’ve even created a spreadsheet that we keep updated. Never buy a list because most of the time they are out of date.

CC: I use Mailchimp and have built my list with the help of Hunter.io, Linkedin, reading mastheads, keeping an eye on who other photographers mention and follow on Instagram, my agents, and asking the communities I’m a part of if they can share contacts from specific brands/publications.

Link to this anwser.

EG: First of all, your IG is your IG. There is no rule that you have to do X, Y, or Z. However, I do feel like it’s an important marketing touchpoint for people to see what you’re about. Even if that is all personal photos of your cats, or whatever. IG will probably be the first place a new viewer will investigate you, so keep that in mind. I think if your IG shows your personality (with personal photos or with work photos), then that’s good enough.

CC: It sounds like you’re sharing what folks expect from a photographer’s Instagram. I know artists who, thanks to Instagram, have gotten job offers. I look at Instagram as an opportunity to keep folks updated on what I’m up to and gain insight on what I’m about, beyond my curated and designed website. It’s another avenue for people to see and find my work thanks to other people sharing and tagging, in addition to newsletters, editorial work, awards, etc. It can have as much of an impact on your marketing efforts as you make it so it’s really up to you how important you make it. Your website is where all your best work lives, but how do people find your website?

EG: I think about marketing quite a bit. I like to send emails and introduce myself to potential clients and other people who are doing cool work. You have to build your network in order for that network to pay off for you. I don’t have an established workflow for it, but if I find out about a new agency doing cool things from a blog or Instagram post, I try to find out who the art directors are and send them postcards. Maybe I’ll email them and try to set up a meeting. It depends on how much free time I have and how brave I’m feeling that day.

And that hits an important point. You have to be brave. You have to learn to put yourself out there and not get a response from someone. In general, you’ll reach out to 100 people and only 20 of them will respond, and of those you’ll only ever meet five of them in person and maybe one of those people hires you down the line two years from now. So you just spent several hours trying to reach 100 people and you failed 99 times. But that one person. . .

JS: Marketing takes up a lot of space in my world. My approach is intuitive, if I have a cohesive batch of photos that I’m excited about then I know it’s time to get them in front of people. Much like Emiliano, I spend a lot of time scrolling the popular mobile app, Instagram, and when I see a magazine or agency that shared some interesting work, I’ll do the deep dive to figure out who was a part of the project. Then I’ll figure out an obtrusive way to get my work in front of them. Since we’re still in a pandemic, I’m really only using email and social media to reach people. The important thing is to make sure that you’re sharing strong work and consistently reaching out to people.

Link to this anwser.

We polled the public on our IG and here are answers from the editors themselves!

JS: As a general rule, I always try to use good grammar and proper punctuation in emails and texts. My communication style is pretty formal and polite. I’ll loosen up a little once I get to know the client but it’s important to always be clear and direct so that everyone involved with the project is on the same page. Also, I like to keep the client posted with updates as the shoot unfolds and wraps. Most of the time things happen as planned but in the event that something unexpected occurs it’s always a good practice to let the client know as soon as possible so that we can create a solution.

EG: I think it’s really important to remember that you are 1 of many dozens of emails they get per day. Say what you gotta say. Be respectful of their time, let them be impressed (or not), and keep it moving. Also, make things easy for them. Make sure the links are easy to navigate, no mistakes, etc. Here’s a pretty basic example of an email I might send:

CC: When it comes to outreach and sharing new work, I think every editor and art buyer likely has a personal preference on the frequency of communication. Personally, I don’t reach out more than once per quarter with relevant updates nor do I expect a response. I trust that if they have the time or desire to respond, they will otherwise I’ll assume they looked at my email and will reach out when the right project comes along. If they responded to every email they received from a photographer they probably wouldn’t get any work done. As far as etiquette, I’m pretty similar to Jared in being polite, formal, and brief. I think there’s a time to be professional and when you establish a relationship with them and get to know them and their vibe it’s easier to be candid and casual. I’ve gained a lot of perspective from listening to Dear Art Producer (thanks Heather Elder!).

EG: You can choose to market yourself with big, loud tactics. I’ve chosen a slower approach with my marketing; I’ll call it “white noise marketing.” The secret for me has been to continue to produce quality images and quietly remind people about them. I do this with a combination of the following:

I’d hate to be the photographer version of a used car salesman with loud gimmicks and cheap suits. That’s not the association I want people to make when they think about my work.The focus for me has always been and will always be “make good work.” Of course, I can do things to help promote that work, but if it sucks to begin with, then I’m failing. I’ll continue to self publish and create personal work—that is essential to me as a human and as a brand.

JS: Self-initiated projects are the cornerstone of all my marketing efforts. This provides a space where I can experiment, push a new aesthetic and explore an area of interest. In this space, I have full control and I am able take more creative risks in terms of approach and presentation. This is the work that I prefer to share when I approach both existing and potential clients.

In terms of marketing practices, it is imperative that I’m sharing work that I’m excited about and presenting it in a way that speaks to my personality.

I do the following:

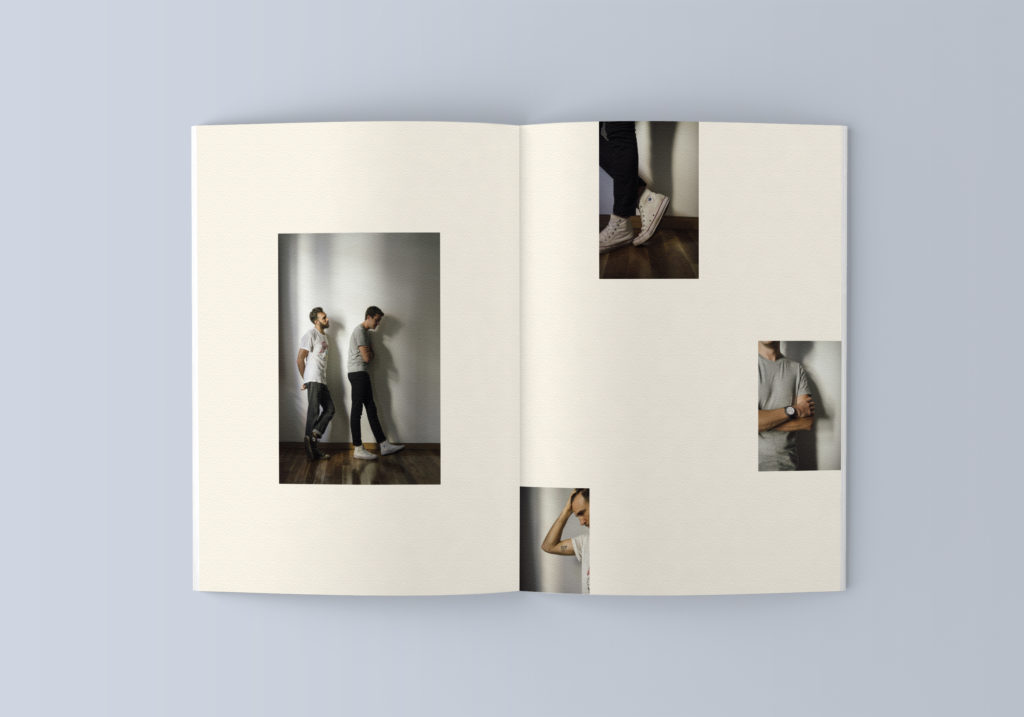

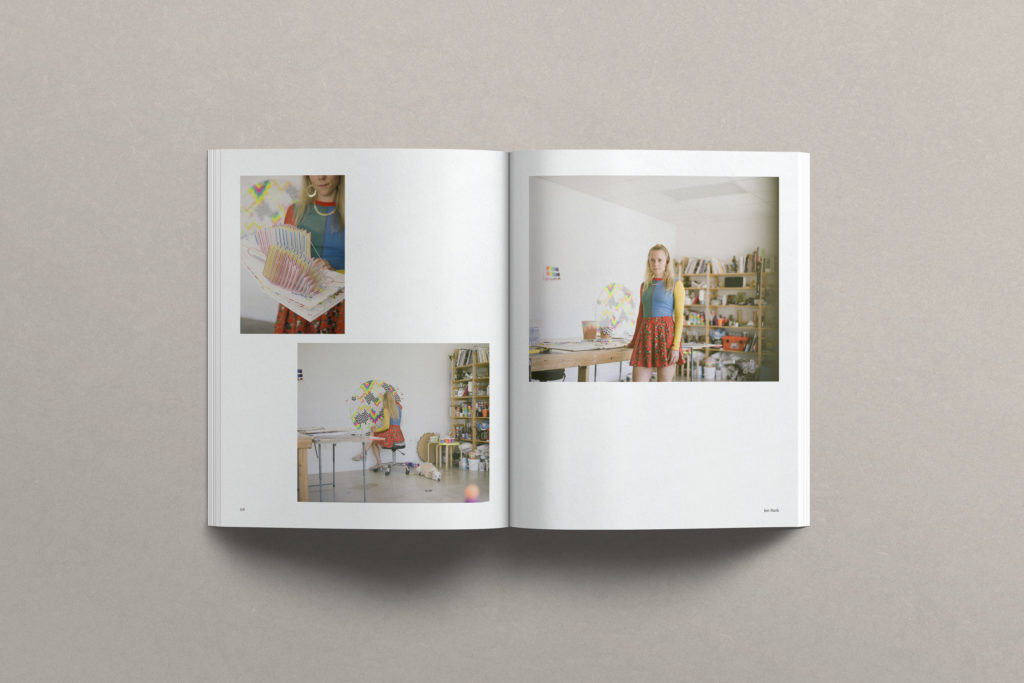

CC: I do the same thing as Jared as far as marketing efforts. Except I don’t have the graphic design skillz so I hire designers to help. Some examples of my printed pieces and projects below –

A client received the above promo and I didn’t hear from them until they hired me for a two-day ad job nine months after receiving the promo. You just never know.

CC: My 11×17 double-sided matte inkjet printed screw post portfolio (will likely switch to a smaller format once in-person meetings are a thing again because that was a pain in the ass to travel with and ship), recent work/image libraries/motion/personal work on an iPad, and leave-behinds (latest promo, postcards, etc). The iPad is helpful if a client comments on an image in the printed book and you can show them the expanded campaign or project on your iPad. Think about what anecdotes you can share related to the projects or images that you’re showing that can give the client insight into your process and abilities. Bring questions based on the research you’ve done about the client beforehand.

EG: Portfolio and winning attitude.

JS:Bring your portfolio, in-progress projects, your ideas and recent work. Also, it helps to brings questions. This is your opportunity to get to know the client. It is also a situation where you can present your work in a way that it can’t be experienced digitally. Show the clients something that they can’t see on your website or IG.

JS: Be the expert in the room, you need to have a solid understanding of the topic/issue/subject before you log into your email. If you’re proposing an idea to a magazine or a news organization, you need to be able to succinctly convey what the idea is, why it’s important and why it fits with this particular publication. Also, be able to mention, why you are the most qualified to tell this story. The more specific that you can be, the better. If you have examples of photographs related to the idea, its best to attach 1-3 of your strongest images along with 2-3 paragraphs describing the project, how it relates to the client and your approach. Also, be sure to acknowledge the recipient’s humanity, it’s okay to add a “good morning” or “good afternoon” at the top of the message along with a compliment about a recent project that they worked on that you enjoyed- this demonstrates that you are paying attention.

CC: Here is some amazing insight from Yael Malka – Want to Pitch To Magazines? & Pitching The New York Times. Also, from multiple editor’s perspectives – Do’s and Don’t of Pitching to Photo Editors. While there is a lot that goes into it I wanted to quote Yael from when she worked at The Fader on what not to do, as a starting point –

Link to this anwser.A lot of photographers would send a very lazy email: ‘Hey, let me shoot this person for you.’ It would be presumptuous, and a lot of the emails weren’t very thoughtful. It was just, ‘You’re a music magazine. Let me shoot this person who’s a musician and that’s all I have say.’ But there’s a lot more to it. Photo editors want to see that you’ve been thoughtful about it—thoughtful in that you have an angle, and thoughtful in that it makes sense for the publication.

JS: A newsletter should be another extension of who you are and what your work is about. It is more than okay to show your personality through the design and voice of it. I like to have at least 3 strong items to share plus a call to action. This could be an editorial assignment that you’re fired up about, a gallery exhibition that you’re participating in, a write up about a project on a website, an in-progress personal project- pretty much anything that is hitting the quality marker and that you’re proud of at the moment. Also, it is important to mention your location as well as your contact info both items should be easy to access. Here is one that I sent earlier this year.

CC: Jared pretty much covered it all, my newsletters are very similar. I try to pick three projects and a few images so recipients can still get something if they look at it for 5 seconds and don’t click to see more or read. You can see my most recent ones here and here.

EG: Every time someone interacts with you, your images, or your brand, you want to reinforce the things you think are the best about you. You should have a clear vision of what your brand stands for and what that looks like. Your newsletter (and everything else in your arsenal) should be in line with that. Some of my most recent newsletters here and here.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Generally speaking.

Photo Editors – Work at magazines. When you’re starting out, getting to know Photo Editors is your main job. They have long lists of other talented photographers and they try to pair a few of them with jobs that line up aesthetically.

Photo Directors – Work at magazines. They’re the big boss. They oversee the photo department, ie all the Photo Editors.

Art Buyer – Work at ad agencies. This title is kinda “old” now and they’re usually called Art Producers.

Art Producer – Work at ad agencies. They research, connect with, and recommend photographers to creative teams (Art Directors). It’s their job to pair a photographer to a project that needs a certain style. They collect bids (ie estimates) from photographers. Usually, they have to bid at least 3 photographers and they may even tell you that you are the “agency recommend.” Ultimately, the agency has a presentation where the 3 photographers are shown and a client chooses which one to use.

Producer – Most commonly, this is a person that is hired by an ad agency or a magazine (with healthy budgets!) or by you to be the producer “on the ground.” They are in charge of staying on schedule, booking the caterers, booking the talent, making sure the RV is there on time, etc etc. They deal with all the hard logistics of a shoot. But there are producers for video, for retouching, for pretty much everything, so the title sometimes gets confusing. For our purposes though, they are people that ensure sh*t gets done on the day of the shoot.

CC: Typically my first point of contact for jobs are Photo Editors and Art Producers. I’ve also spoken to Visual Editors, Creative Directors (at startups or smaller companies), Producers, Photo Directors, Integrated Producers (work at ad agencies and produce both motion and stills), Design Director, Photo Publicist, etc. It doesn’t hurt to talk to a variety of folks because you never know where they’ll be next and whether they’ll have the responsibility of hiring or recommending photographers. If this feels overwhelming, stick to a few titles but you never know how your name will end up in the hat.

Link to this anwser.

EG: You can choose to market yourself with big, loud tactics. I’ve chosen a slower approach with my marketing; I’ll call it “white noise marketing.” The secret for me has been to continue to produce quality images and quietly remind people about them. To do this, I like to send people anywhere from five to eight postcards a year and usually write something funny and personalized on the back. I’d hate to be the photographer version of a used car salesman with loud gimmicks and cheap suits.That’s not the association I want people to make when they think about my work.

The focus for me has always been and will always be “make good work.” Of course, I can do things to help promote that work, but if it sucks to begin with, then I’m failing. I’ll continue to self publish and create personal work—that is essential to me as a human and as a brand.

JS: This feels like a cart versus horse query. From my perspective, you need to have the goods before you share them. My focus will always be creating new projects and presenting them in a way that is fully in service of the work. When my work is ready to be shared with clients, I try to be personal and tailored in the marketing approach. This could be in the shape of a direct email or a handwritten letter with a batch of small prints in an envelope. I want the way that I’m reaching out to be consistent with who I am as a person and the feel of my work. Photographs will always lead. Design needs to be utilitarian and current. No gimmicks, no food. Ask yourself these questions, does this feel like me and would I want to receive this?

Link to this anwser.

EG: Everyone struggles with this! But let’s think about this pain as an opportunity to unpack why it’s so hard, though. I think the pain is not really about choosing the best photos. The pain is about figuring out ‘Who am I and what do I want to say?’ So when editing down your pile of photos, repeatedly ask yourself “Who are you and what do you want to say? Does this image support or enhance that vision I want to create?”

Here is a clip of me talking to one of my mentees about the difficulty and the value of editing your portfolio. Sorry I’m not as beautiful as young Leo.

JS: I really want to drop an updated version of the Ernest Hemingway quote about writing and bleeding at a typewriter. In all seriousness, editing can be a difficult and often lonely task. As I write this, I’m trying to motivate myself to put together a new edit of some portrait work over the past 2 years. I share this to say that even 10+ years in the biz, the task of breaking apart my work, figuring out what is successful/unsuccessful is still daunting and challenging. Beginning the process of editing is a lot like trying to floss daily or even jogging, both of these are activities that you don’t really look forward to but you know that they’re necessary. For me, I like to start with a couple of questions- “What’s this work about, and what do I want to say?” Be ruthless with your image selection- “does this image help advance your story/aesthetic?” LESS IS MORE. Having 8 incredible photographs with a consistent aesthetic will always better than a potpourri gallery of 17. Good editing takes time. Rome wasn’t built in a day and neither will your portfolio. Set a realistic deadline so you don’t put off this process. Do a little bit here and there, hit up a peer or 2 and over time the work will let you know when it’s ready to be out in the world.

CC: Because we’re often emotionally attached to our work and we know what it took to make certain images or think that a certain image should be included for whatever reason. I love the advice Emiliano and Jared gave above. Also, about 5 years into my career I hired someone to help me edit my portfolio. It was interesting to see what they ended up with and they noticed through-lines in my work to help it feel cohesive in ways I didn’t. In hindsight, I was at a point in my career where I wasn’t sure what I wanted to say and I let the editor mold my portfolio into what they thought it was saying which was helpful at the time. Since then I’ve had good and mediocre experiences with hiring editors and my friends have as well. Take any feedback and advice with a grain of salt, everyone’s opinion about your edit will be subjective. You know what you want to say best so if you work with an editor, make sure this is clear to them or you’ll have a frustrating experience. Think about what you want to say and where you want to go with your career and ONLY show the work that demonstrates this. Eliminate redundancy, your portfolio needs to be a succinct edit that also shows the breadth of your skill and clearly communicate your style. If something doesn’t fit in with the rest of your work it’ll only confuse people or dilute the existing work.

Link to this anwser.

CC: I still struggle with doing this on my own but here are some resources I’ve found:

A Photo Editor – $free – use the search function to find relevant examples like “pricing buyout” “pricing social media” or browse through to see the thought process and context for commercial estimates. I used to cobble together estimates using these examples.

Wonderful Machine or other Consultants – varies, WM is $150/hour, they take over the estimating process on your behalf.

Photo Agents – $free initially, 25%-30% commission if you win the job, they take over the estimating process on your behalf.

Getty Images Calculator – on the high end and doesn’t consider volume since you’re calculating a single image price.

fotoQuote software – $150 one time purchase – industry-standard photo Pricing Guide with licensing

Blinkbid software – $16/mo or $168/year subscription – bidding, producing, and invoicing

JS: In addition to the resources that Carmen shared, another approach is to ask if the client has a budget in mind. If they do then you can take that number and run it through the calculators above and or your personal network to arrive at a fee based on the usage.

EG: First, let’s identify why I, personally, would want to shoot film on a job. For me, the combination of the cameras, the lenses, and the film ‘look’ create a certain picture quality that I still can’t really replicate with digital cameras. Also, I tend to shoot almost exclusively medium format film. Those cameras are slow and clumsy, so they force me to go into a mental zone that is hyper focused, methodical and way more intentional. I really enjoy that space and feel like the images are better, afterwards. Whether that’s true or not is 100% subjective, but that’s just how I feel. So if a job feels like it could yield some especially powerful imagery, I will try to shoot film if the logistics allow for it.

Everyone will have their own reasons for wanting to shoot film, and it’s important you identify why you’re even complicating things for yourself!

Once you identify that you’d like to shoot film for a certain project, now it’s time to get that approved by the client. Some clients will love the idea and embrace the added complications. For some clients/jobs, the answer will be ‘absolutely not.’ And maybe some jobs will allow for a hybrid shoot with some shots on film, but most on digital, or something like that. Every job will be different.

In order to get approval, you’ll most likely need to let the client know how much it costs and how much longer it will take to see images. This is really as straightforward as estimating how many rolls you will shoot, what that costs to buy/develop/print/scan and put that into an estimate. On bigger jobs, you may be able to add a little on top of those costs to cover the time to buy, run to lab, etc etc. Something like a 20% markup on top of the actual costs. For example, one roll of Kodak Portra 400 costs $10 to buy and $20 to develop and scan (medium res). If I anticipate shooting 10 rolls on a job, then it’s $30 x 10. You may need to add a high res scan on top of that or an actual c-print if that’s your process.

An example from an actual estimate below:

Example shows a 2-day shoot where I would rent two cameras and shoot an estimated 20 rolls of 120 per day @ $35/roll

Obviously, on a bigger shoot an added cost of $1900 is not that much. But for smaller shoots, it may be problematic.

Link to this anwser.

EG: We can’t answer questions this specific on FG, unfortunately. But we can provide some basic guidance for licensing questions, especially since they come up so often. I will say I see people doing this “the company is worth $XXX and they’re only offering $XXX” framework quite often. Remember that even though the company might be huge, they have many, many different tiers of marketing efforts and agencies they engage with. Sometimes the budget really is only $1000 because its some silly marketing push for them or you’re working through their below-the-line or social agency and budgets are REALLY small at that level.

I’m not proposing you accept what doesn’t feel right, but I just want you to consider that maybe $1000 is a lot of lattes for an image that is meaningless and gathering digital dust. Depending on what the project is, what kind of image we’re talking about, and exclusivity/usage, $1000 may be a fair price, tbh.

For a more in-depth answer to how to figure out licensing fees, we’ve answered that HERE.

CC: I actually don’t think $1000 is that bad and the reason is that it’s only being used on the internet. Usage is key here. A quick plug into the Getty calculator and I got $1,475 for worldwide digital media advertising usage. The calculator doesn’t have a perpetuity option but up to 3 years gives you an idea. Most brands will likely refresh their images in that span of time. Some people say to triple your 2-3 year usage for usage in perpetuity. The calculator also gives numbers that are typically on the high end, from my experience. Just for fun, I plugged in OOH, print, and tv advertising worldwide for up to 5 years and the rate is $23,680. Again, usage is key. When in doubt, get in touch with a photo agent or refer to the links that Emiliano shared above. Also, you don’t have to accept the first offer. Counteroffer and see what happens. Worst case scenario is that you’re back to $1000, the best-case scenario is that they are willing to pay more because the image is that unique and that valuable to them.

EG: Your creative fee should remain the same. Simply charge for the film costs and any other production costs associated with shooting film. The film is simply a production line item just like a c stand or catering. See this question for details.

Link to this anwser.

EG: In NYC and LA, you can be paid anywhere from $200-$650 as a photo assistant. $200 being very low, $300-$350 for an editorial job with an established magazine/photographer, to $500-$650 for a full commercial rate as a first assistant. I’ve heard of realllllly experienced assistants getting a little more, but that’s pretty rare. Some assistants will get some jobs as “lighting designers” and that can pay $1000 or more.

Other markets are usually about the same range, as far as I know. In my experience, assistants in other markets are less flexible with their rates since they probably don’t have a personal relationship with the photographer coming in from out of town (me) and they have less jobs per year, so can’t afford to be flexible.

CC: One thing I want to add to Emiliano’s answer is to keep in mind that if you offer a very low rate to an assistant, even if it’s “quick and easy” or just helping you carry gear, like yourself they can’t book anything else that day. My personal rule is not to pay less than $300 and if the editorial budget is less than that then I pay out of pocket. For commercial jobs, I inform the client and budget as Emiliano suggested above. I used to work with photographers who would hand me a check at wrap and I really appreciated that. Let the assistant know your payment terms when hiring.

Link to this anwser.

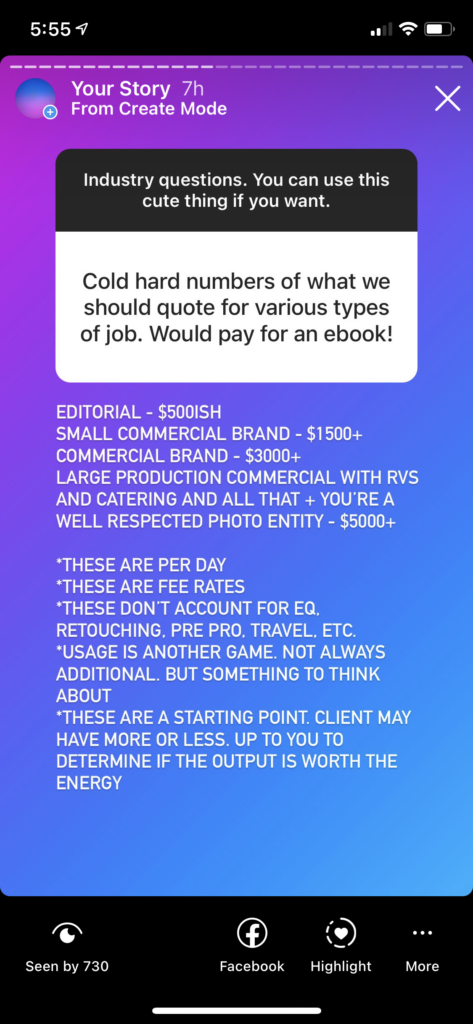

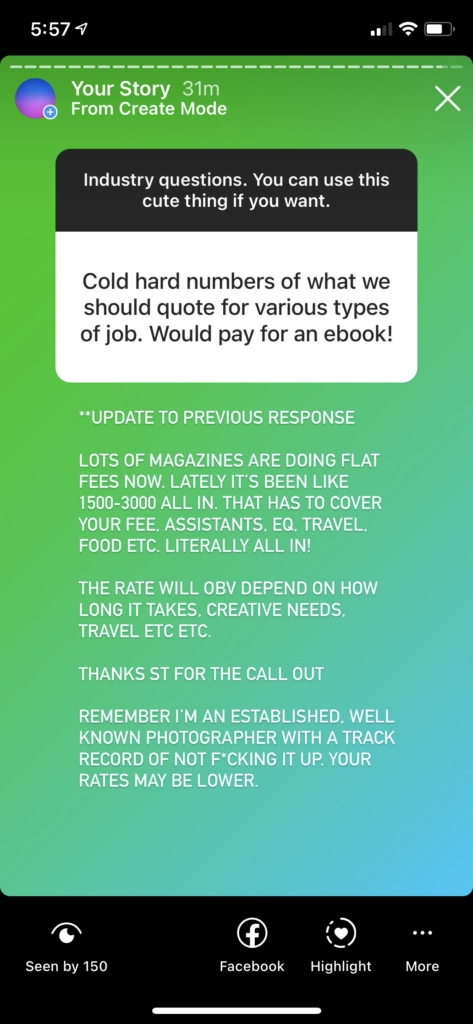

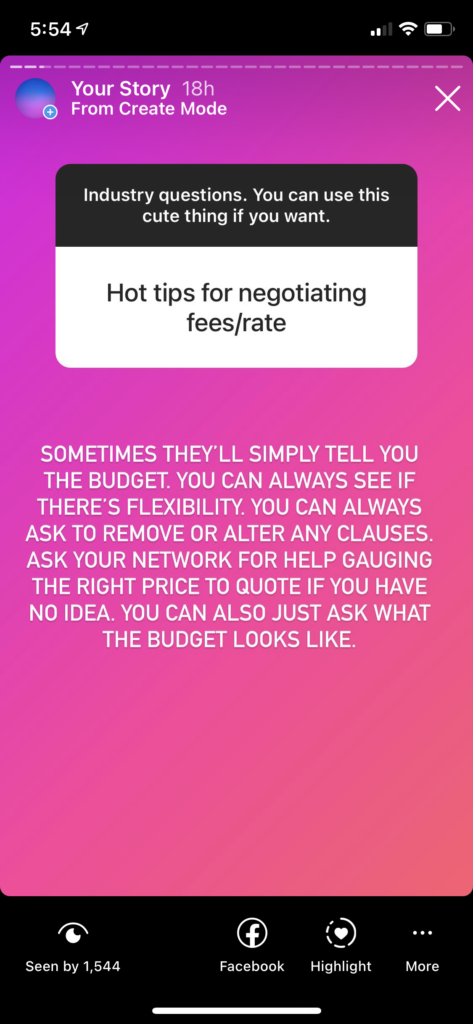

JS: For editorial, the rates are set by the publication and they can fluctuate from $500 to $1500 not including expenses (travel, meals, assistant, equipment, etc). In terms of commercial projects, the rate should be dictated by the usage- the more usage, the higher the rate- again not including expenses.

EG: From my IG stories.

CC: The numbers that Emiliano shared above are spot on based on my experience. If a client asks you this question, my next questions are always “Can you tell me how many images will be delivered, how and for how long the images intend to be used? Is there a budget outside of the day rate for expenses (assistant, equipment, retouching, etc.)?” Ask for help and make sure it’s a fair exchange.

Link to this anwser.

JS: Personal work is the container that allows me to show who I am and what I care about. Also, it is a space for me to experiment. When I am reaching out to clients, the majority of the work that I share is self-initiated either a 1 one-day test shoot or a longer-form narrative project. This industry is evidence-based and you have to demonstrate that you can deploy a specific approach on your own before you’re hired for it.

CC: I learned the importance of test shoots when I was assisting. Even though the photographer I was assisting was working a ton, she still found time to test on her one or two days off and that’s the work that clients would see, love, and hire her for.

I’ve experienced the same thing – immediately after sharing a test shoot, a client used one of the images from it as a reference for the work they wanted me to create for them.

Tests give me an opportunity to collaborate with different crew members and build a team. Every job is going to have different needs and the more people you work with the more you can confidently bring on the right people for the job. If you want to work with a crew, put together a mood board and reach out to people. Be specific about what they’ll receive in exchange for contributing their time and talent, ask about how they work and if they require a kit fee (HMU) or return fees (stylists), where the images intend to be used, and credits.

Nobody has the same perspective, ideas, and life experience as you. Personal work is what will set your work apart from everyone else’s. Also read “What are the elements of a successful personal project?”

EG: Personal work yields editorial/commercial work. That’s just a fact.

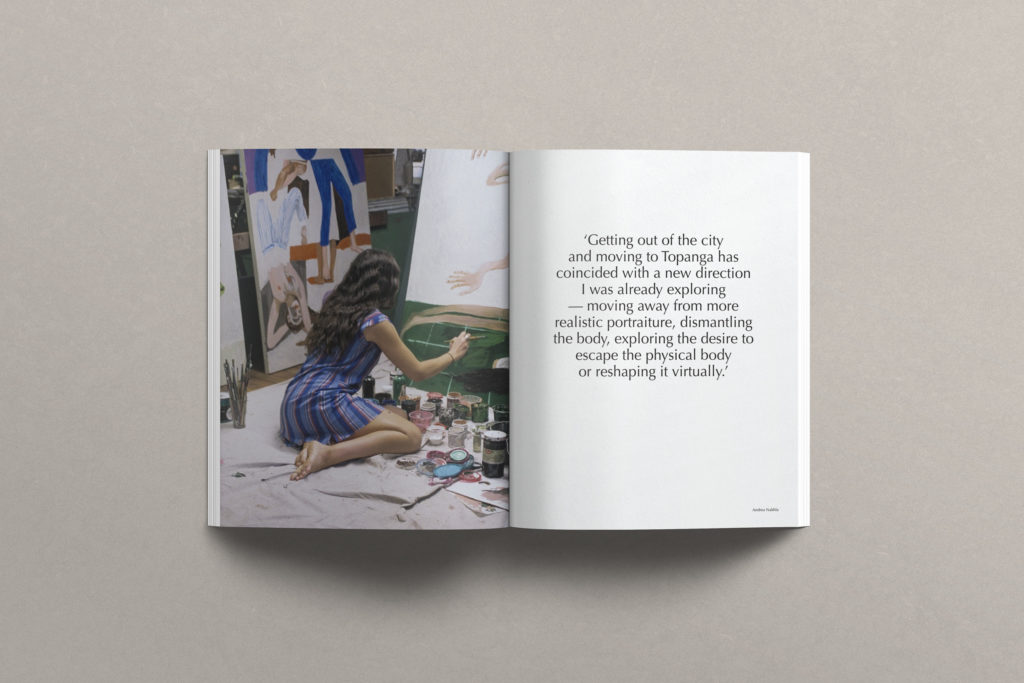

A lot of people talk about making personal work only as a means to an end (ie commercial work). That sounds like a chore, not something you’re personally invested in. For me, personal work was something I needed to make. I was going to make the work regardless of anyone paying attention. If you don’t pour yourself into your personal projects . . . why are you even doing this?

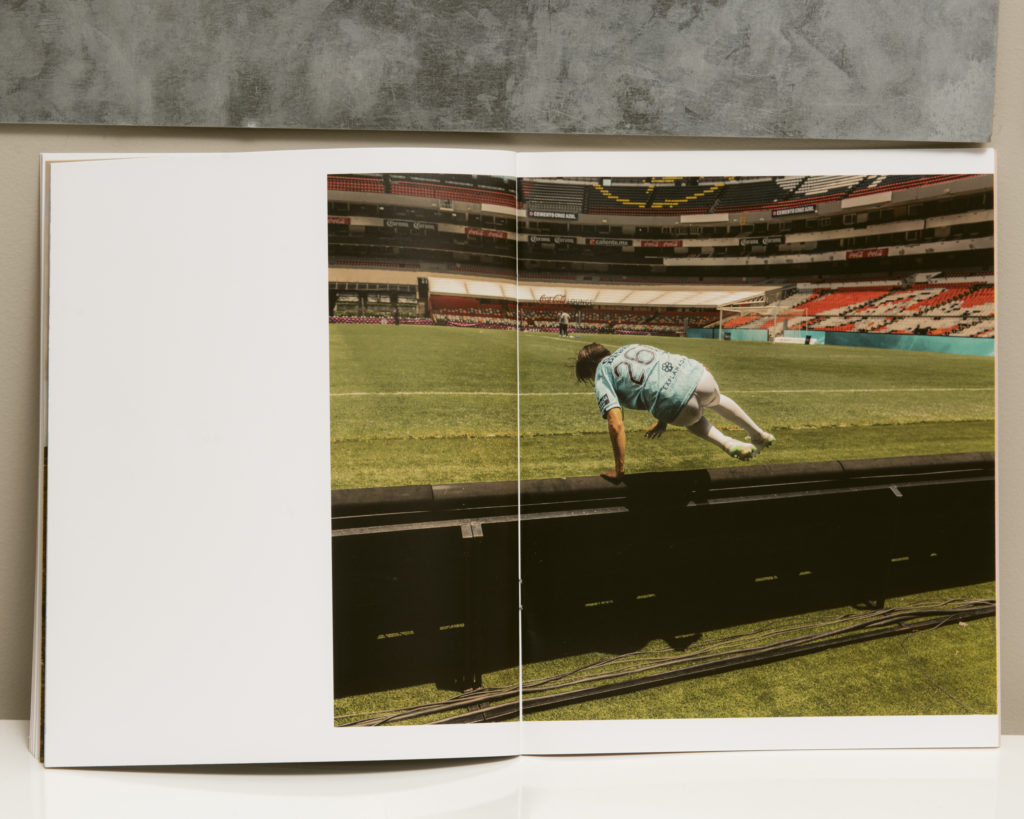

JS: Personal work is the lab where you cook up and make a mess with different experiments. I often use smaller self-initiated projects to figure out and refine different approaches that I will either use in a longer term project or for an editorial client. The relationship between commercial and personal work is symbiotic, I’ve found that I’m often hired for a specific approach that I honed during a project that I pursued on my own. Always remember that the main through line with your work is YOUR VOICE- don’t get tripped up on if it is too much of a departure from your past work.

EG: If you’re not crafting new things and experimenting . . . then why are you even here??? Personal work is where you experiment and try out things you’ve been wanting to do. It also is the only time that you can be 100% selfish and do the work YOU want to do. No one else has a say in what you make. If you do personal work right, then assignments will follow in the same style as your personal work.

Link to this anwser.

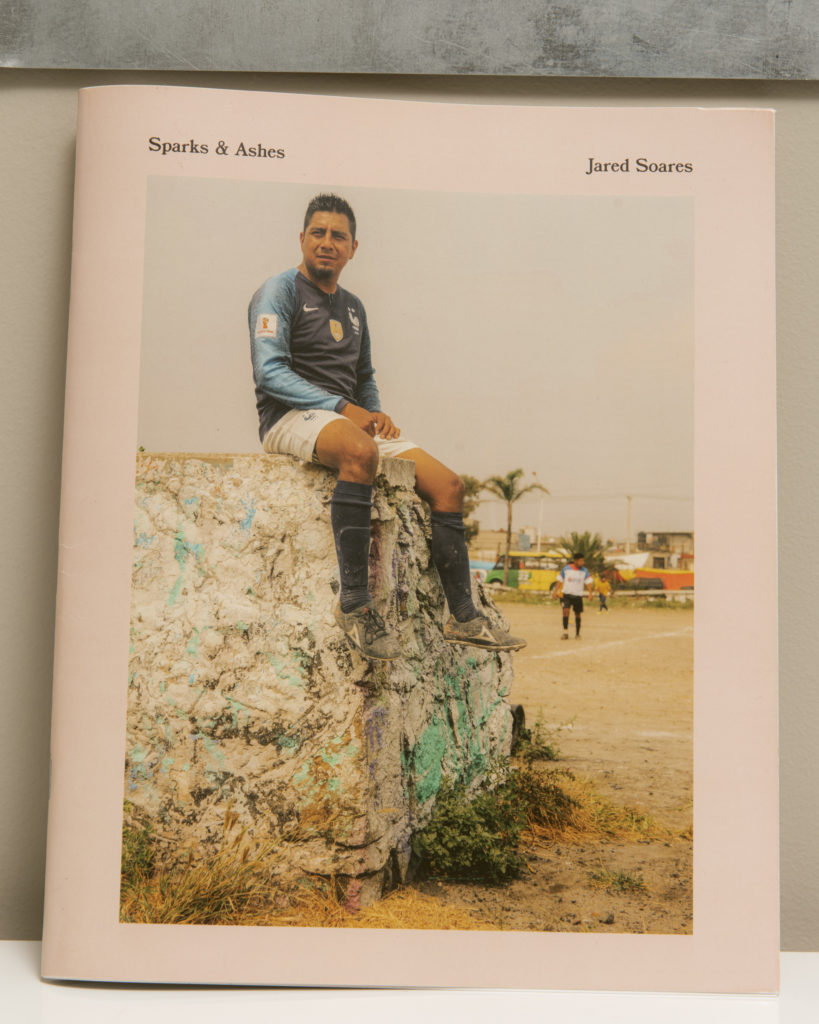

JS: A successful personal project, from my perspective, should be about something or someone that you care about, it’s much easier (and exciting) to make photographs when you are invested in that particular topic, issue, or community. The project should be a vehicle to showcase your aesthetic and the images should be presented the way that you see fit. It should also be about discovery, you should be learning during the process. A printed piece, a pop-up installation, a project-specific website, a hashtag, are a few examples of ways to present and distribute a body of work. Field time for my projects has varied based on the topic: 10 years, 2 weeks, and 2 days. Time is always a good thing but it doesn’t always result in a worthy project.

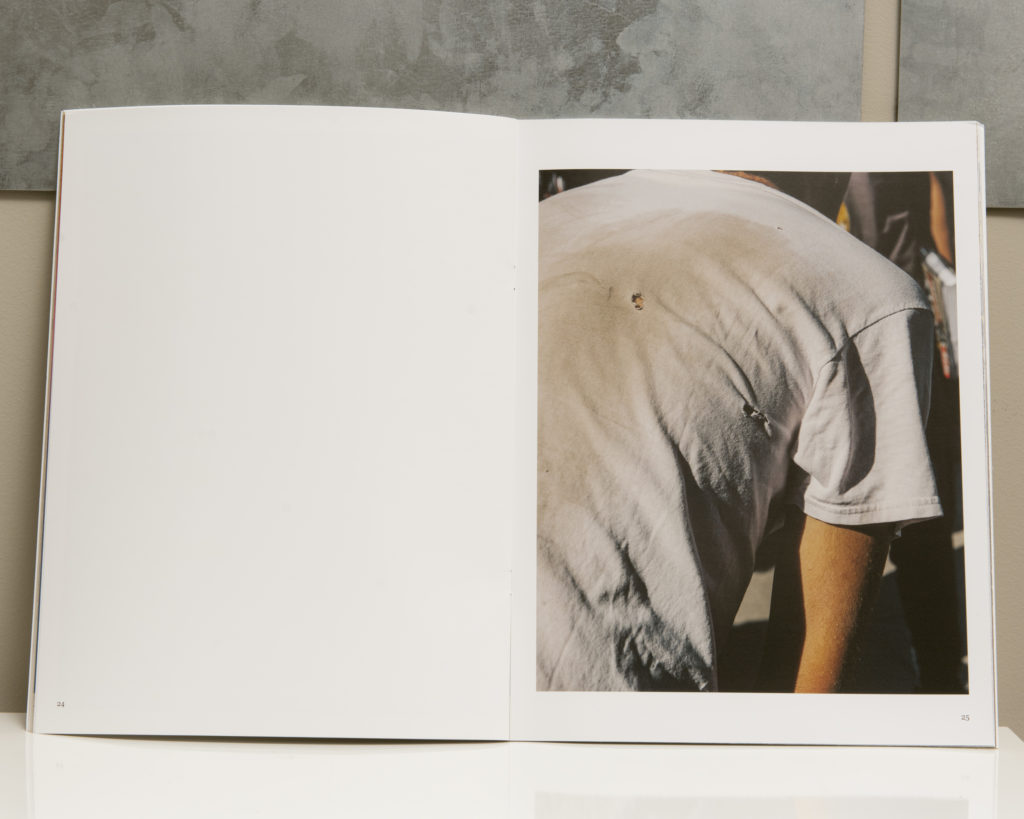

Self-initiated projects represent who I am as an artist. This type of work is the foundation that drives me to make photographs. Small Town Hip hop, The Farms, and The Skaters of La Paz are all examples of my personal work.

EG: Beyond what JS said, it should ideally represent the type of work you want to make. Every assignment will have an agenda that isn’t necessarily your agenda. A personal project should be 100% about your agenda.

CC: One project I found to be successful because I was able to demonstrate a new approach to lighting in studio. Another project was successful because I was able to tell stories and create images and compile them into a self-published book that I wanted to see exist in the world. Another was successful because I was able to stretch myself and direct, DP, and edit a motion piece. All this to say, I have found success in personal projects when I felt that I was able to do something different from what I typically do when I’m commissioned and stretch myself to apply a new skill or create something I hadn’t done before. I think a personal project is successful if it yanks you out of complacency to create work that tells people more about you (personally/stylistically/artistically). Naturally, this will be something you’re excited to share, and maybe someone will see it, be inspired by it, and hire you to create something similar for them. But, I see this as a bonus by-product of the project and it’s not my motivation because what if you don’t receive any response?

Link to this anwser.