Questions

Knowledge Base Questions

We polled the public on our IG and here are answers from the editors themselves!

EG: My process is pretty straightforward. I drop off film at the lab and they give me pretty big scans of the entire shoot in about 3 days. That goes into the computer and its just like a digital shoot at that point. If the client needs a bigger file, then I may do additional high res scans of the final files.

You have to communicate what this will look like to the client. I live in NYC, so I can run to the lab pretty much the same day and in 2-3 days have decent scans ready to go. But your location or post processing process may differ. I find that 2-3 days is not really a deal breaker for most situations.

Link to this anwser.

EG: For sure. I personally don’t like to mix too much because my brain gets confused, but if you can identify scenarios that you like for digital and others for film or just shoot a mix at all times, then go for it. I’ve definitely shot mostly digital before and when a situation is really hitting hard, then I grab the film camera. I’ve also brought my digital camera to use as a polaroid. Adjust. And then move to the film cameras. I’ve shot A LOT of film in my life, so I’m pretty confident in my cameras and my ability, but it’s ultimately about shooting a ton and believing in yourself!

Link to this anwser.

EG: Your creative fee should remain the same. Simply charge for the film costs and any other production costs associated with shooting film. The film is simply a production line item just like a c stand or catering. See this question for details.

Link to this anwser.

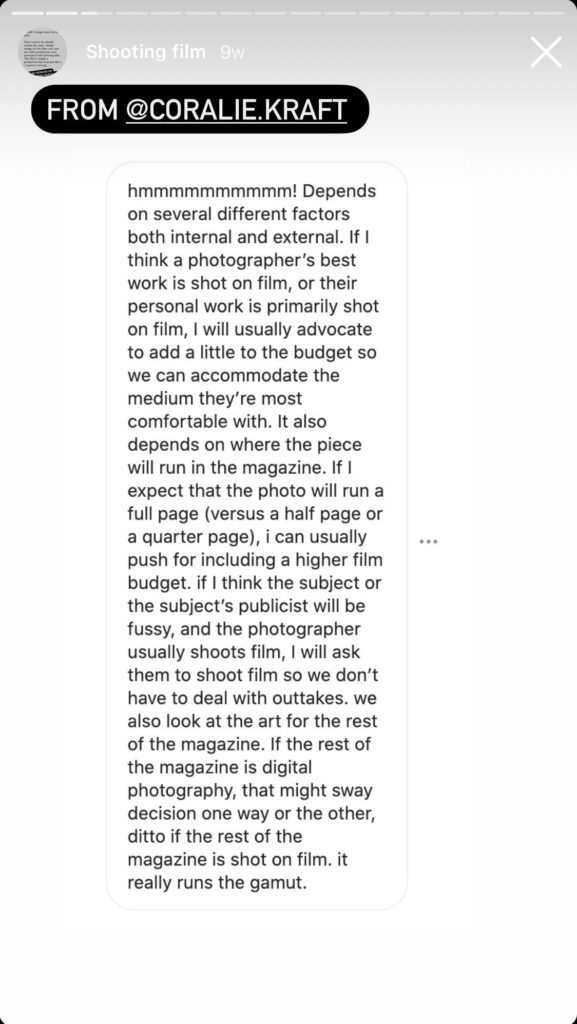

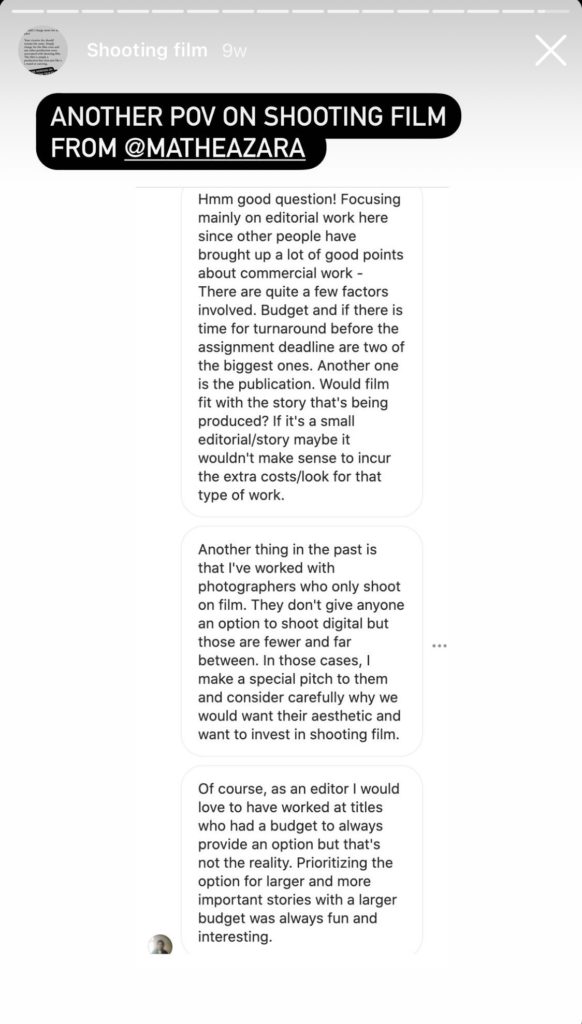

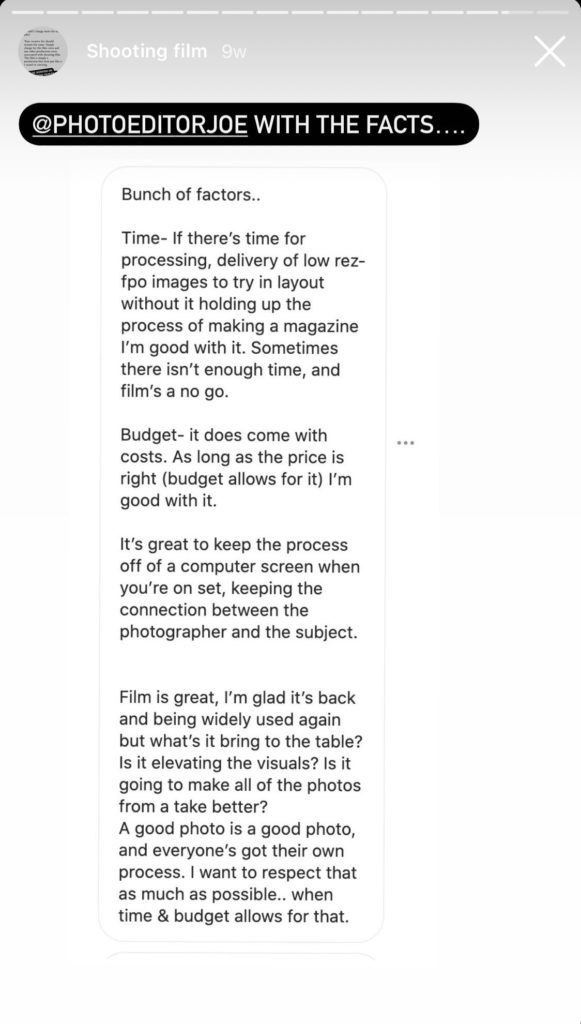

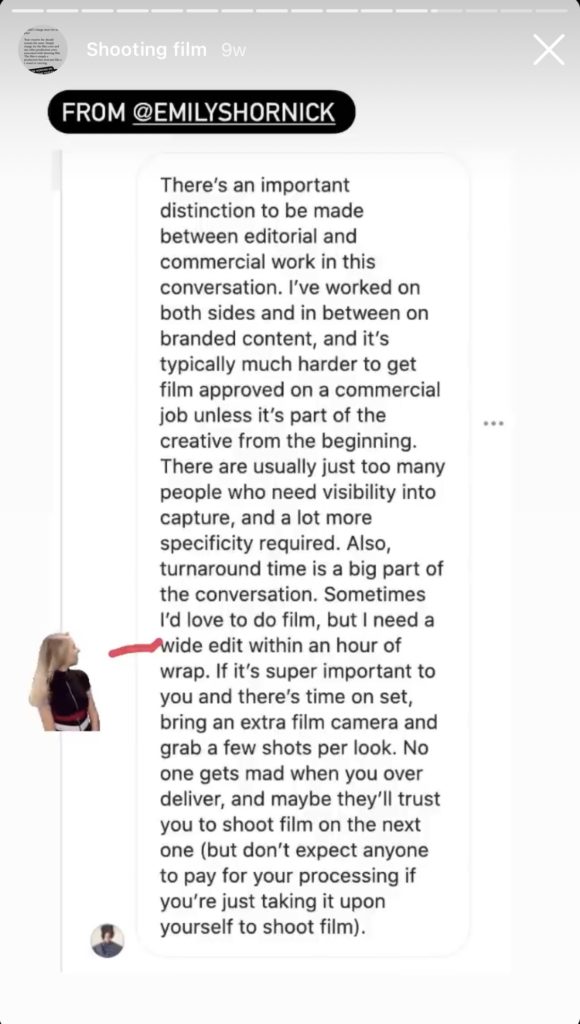

EG: First, let’s identify why I, personally, would want to shoot film on a job. For me, the combination of the cameras, the lenses, and the film ‘look’ create a certain picture quality that I still can’t really replicate with digital cameras. Also, I tend to shoot almost exclusively medium format film. Those cameras are slow and clumsy, so they force me to go into a mental zone that is hyper focused, methodical and way more intentional. I really enjoy that space and feel like the images are better, afterwards. Whether that’s true or not is 100% subjective, but that’s just how I feel. So if a job feels like it could yield some especially powerful imagery, I will try to shoot film if the logistics allow for it.

Everyone will have their own reasons for wanting to shoot film, and it’s important you identify why you’re even complicating things for yourself!

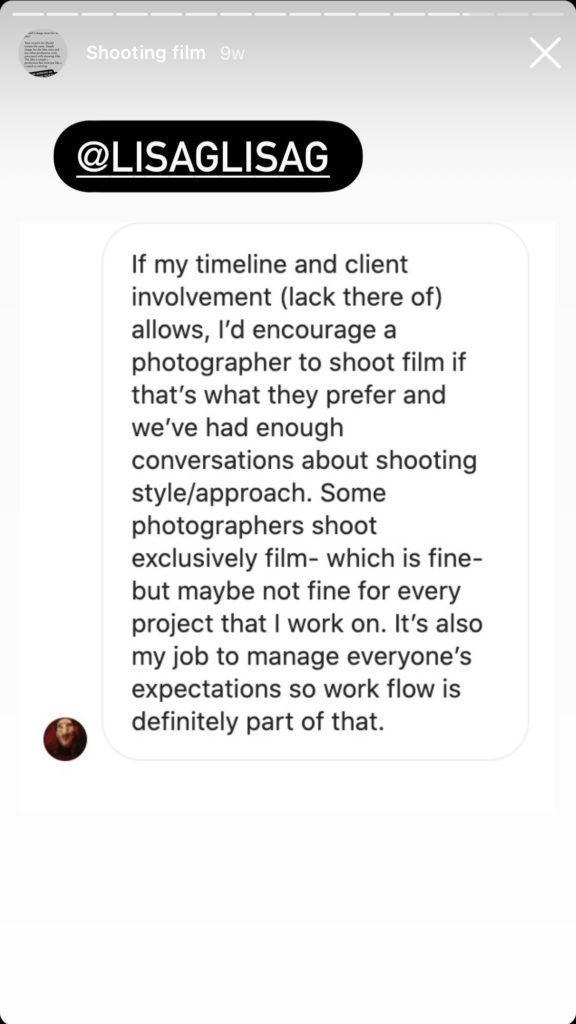

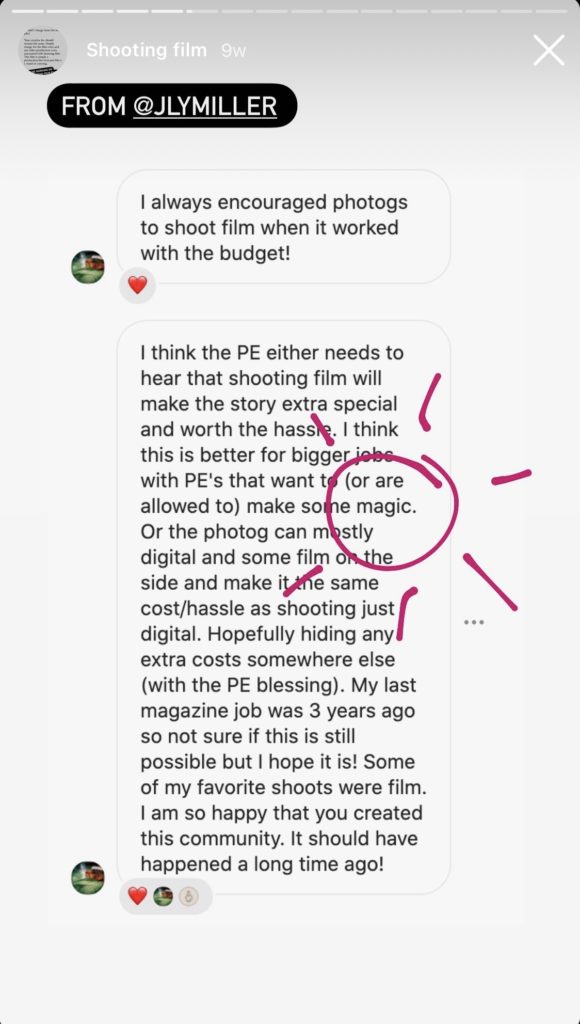

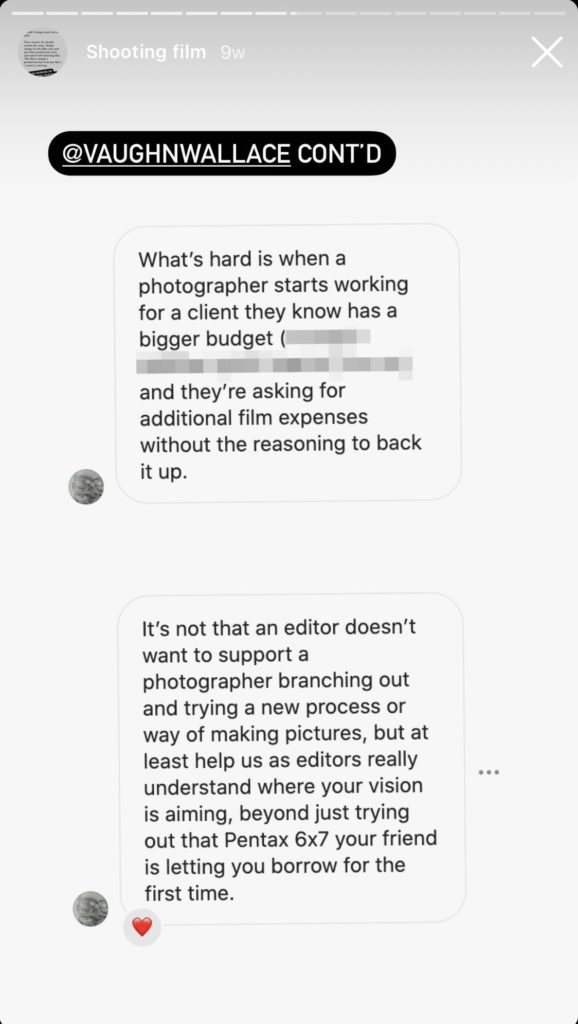

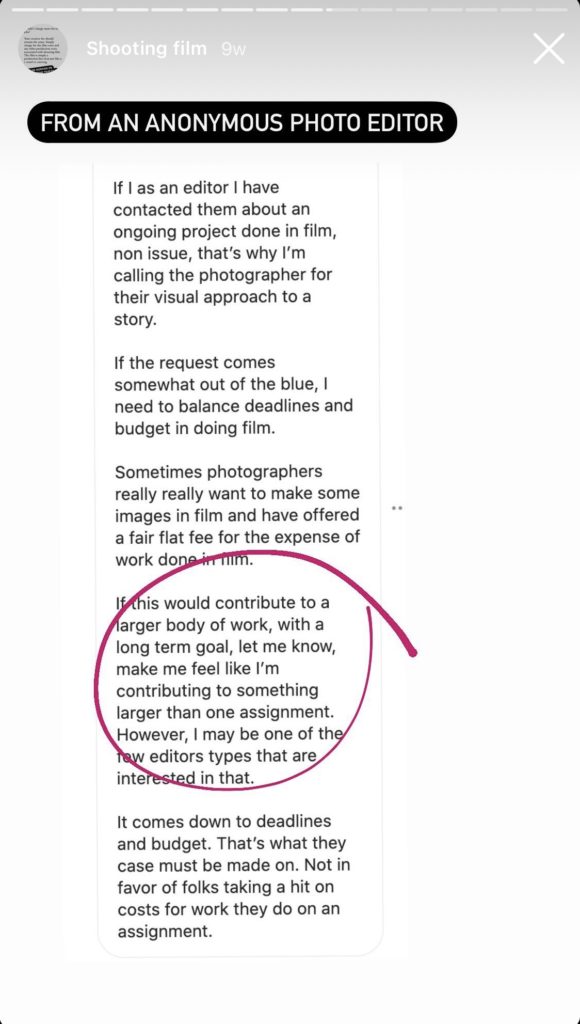

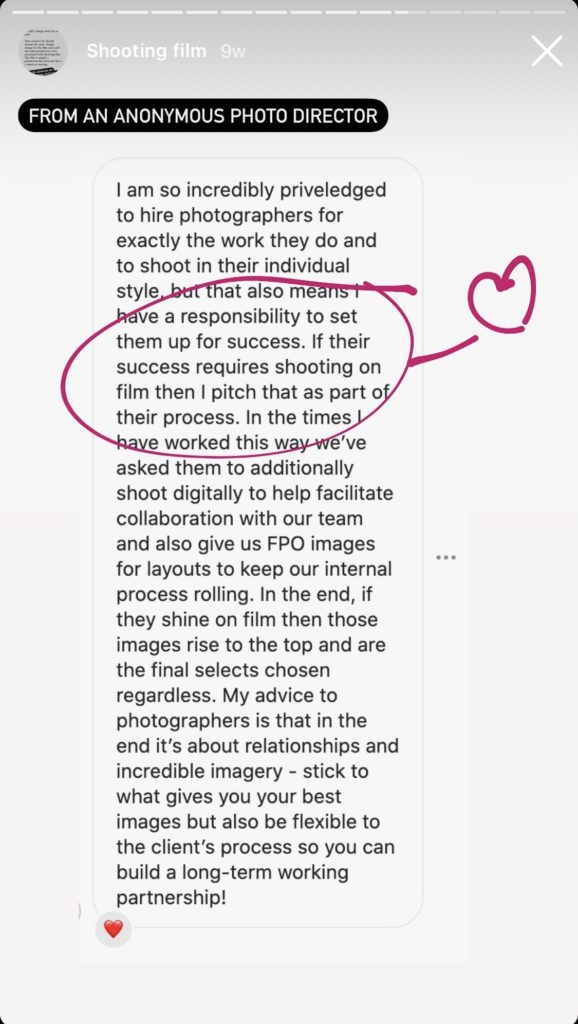

Once you identify that you’d like to shoot film for a certain project, now it’s time to get that approved by the client. Some clients will love the idea and embrace the added complications. For some clients/jobs, the answer will be ‘absolutely not.’ And maybe some jobs will allow for a hybrid shoot with some shots on film, but most on digital, or something like that. Every job will be different.

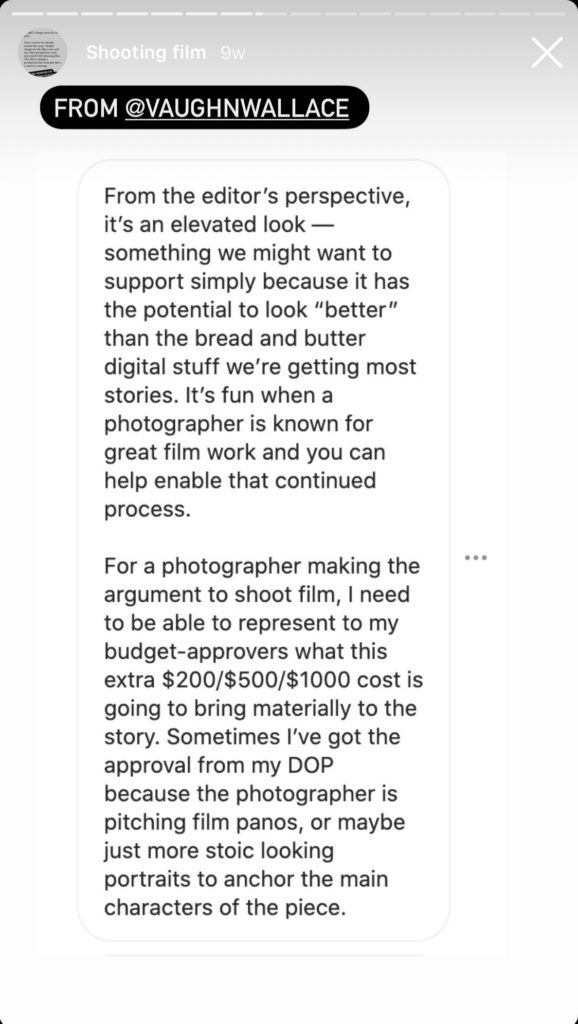

In order to get approval, you’ll most likely need to let the client know how much it costs and how much longer it will take to see images. This is really as straightforward as estimating how many rolls you will shoot, what that costs to buy/develop/print/scan and put that into an estimate. On bigger jobs, you may be able to add a little on top of those costs to cover the time to buy, run to lab, etc etc. Something like a 20% markup on top of the actual costs. For example, one roll of Kodak Portra 400 costs $10 to buy and $20 to develop and scan (medium res). If I anticipate shooting 10 rolls on a job, then it’s $30 x 10. You may need to add a high res scan on top of that or an actual c-print if that’s your process.

An example from an actual estimate below:

Example shows a 2-day shoot where I would rent two cameras and shoot an estimated 20 rolls of 120 per day @ $35/roll

Obviously, on a bigger shoot an added cost of $1900 is not that much. But for smaller shoots, it may be problematic.

Link to this anwser.

EG: We can’t answer questions this specific on FG, unfortunately. But we can provide some basic guidance for licensing questions, especially since they come up so often. I will say I see people doing this “the company is worth $XXX and they’re only offering $XXX” framework quite often. Remember that even though the company might be huge, they have many, many different tiers of marketing efforts and agencies they engage with. Sometimes the budget really is only $1000 because its some silly marketing push for them or you’re working through their below-the-line or social agency and budgets are REALLY small at that level.

I’m not proposing you accept what doesn’t feel right, but I just want you to consider that maybe $1000 is a lot of lattes for an image that is meaningless and gathering digital dust. Depending on what the project is, what kind of image we’re talking about, and exclusivity/usage, $1000 may be a fair price, tbh.

For a more in-depth answer to how to figure out licensing fees, we’ve answered that HERE.

CC: I actually don’t think $1000 is that bad and the reason is that it’s only being used on the internet. Usage is key here. A quick plug into the Getty calculator and I got $1,475 for worldwide digital media advertising usage. The calculator doesn’t have a perpetuity option but up to 3 years gives you an idea. Most brands will likely refresh their images in that span of time. Some people say to triple your 2-3 year usage for usage in perpetuity. The calculator also gives numbers that are typically on the high end, from my experience. Just for fun, I plugged in OOH, print, and tv advertising worldwide for up to 5 years and the rate is $23,680. Again, usage is key. When in doubt, get in touch with a photo agent or refer to the links that Emiliano shared above. Also, you don’t have to accept the first offer. Counteroffer and see what happens. Worst case scenario is that you’re back to $1000, the best-case scenario is that they are willing to pay more because the image is that unique and that valuable to them.

EG: In NYC and LA, you can be paid anywhere from $200-$650 as a photo assistant. $200 being very low, $300-$350 for an editorial job with an established magazine/photographer, to $500-$650 for a full commercial rate as a first assistant. I’ve heard of realllllly experienced assistants getting a little more, but that’s pretty rare. Some assistants will get some jobs as “lighting designers” and that can pay $1000 or more.

Other markets are usually about the same range, as far as I know. In my experience, assistants in other markets are less flexible with their rates since they probably don’t have a personal relationship with the photographer coming in from out of town (me) and they have less jobs per year, so can’t afford to be flexible.

CC: One thing I want to add to Emiliano’s answer is to keep in mind that if you offer a very low rate to an assistant, even if it’s “quick and easy” or just helping you carry gear, like yourself they can’t book anything else that day. My personal rule is not to pay less than $300 and if the editorial budget is less than that then I pay out of pocket. For commercial jobs, I inform the client and budget as Emiliano suggested above. I used to work with photographers who would hand me a check at wrap and I really appreciated that. Let the assistant know your payment terms when hiring.

Link to this anwser.

EG: First of all, your IG is your IG. There is no rule that you have to do X, Y, or Z. However, I do feel like it’s an important marketing touchpoint for people to see what you’re about. Even if that is all personal photos of your cats, or whatever. IG will probably be the first place a new viewer will investigate you, so keep that in mind. I think if your IG shows your personality (with personal photos or with work photos), then that’s good enough.

CC: It sounds like you’re sharing what folks expect from a photographer’s Instagram. I know artists who, thanks to Instagram, have gotten job offers. I look at Instagram as an opportunity to keep folks updated on what I’m up to and gain insight on what I’m about, beyond my curated and designed website. It’s another avenue for people to see and find my work thanks to other people sharing and tagging, in addition to newsletters, editorial work, awards, etc. It can have as much of an impact on your marketing efforts as you make it so it’s really up to you how important you make it. Your website is where all your best work lives, but how do people find your website?

EG: Generally speaking.

Photo Editors – Work at magazines. When you’re starting out, getting to know Photo Editors is your main job. They have long lists of other talented photographers and they try to pair a few of them with jobs that line up aesthetically.

Photo Directors – Work at magazines. They’re the big boss. They oversee the photo department, ie all the Photo Editors.

Art Buyer – Work at ad agencies. This title is kinda “old” now and they’re usually called Art Producers.

Art Producer – Work at ad agencies. They research, connect with, and recommend photographers to creative teams (Art Directors). It’s their job to pair a photographer to a project that needs a certain style. They collect bids (ie estimates) from photographers. Usually, they have to bid at least 3 photographers and they may even tell you that you are the “agency recommend.” Ultimately, the agency has a presentation where the 3 photographers are shown and a client chooses which one to use.

Producer – Most commonly, this is a person that is hired by an ad agency or a magazine (with healthy budgets!) or by you to be the producer “on the ground.” They are in charge of staying on schedule, booking the caterers, booking the talent, making sure the RV is there on time, etc etc. They deal with all the hard logistics of a shoot. But there are producers for video, for retouching, for pretty much everything, so the title sometimes gets confusing. For our purposes though, they are people that ensure sh*t gets done on the day of the shoot.

CC: Typically my first point of contact for jobs are Photo Editors and Art Producers. I’ve also spoken to Visual Editors, Creative Directors (at startups or smaller companies), Producers, Photo Directors, Integrated Producers (work at ad agencies and produce both motion and stills), Design Director, Photo Publicist, etc. It doesn’t hurt to talk to a variety of folks because you never know where they’ll be next and whether they’ll have the responsibility of hiring or recommending photographers. If this feels overwhelming, stick to a few titles but you never know how your name will end up in the hat.

Link to this anwser.

JS: As a general rule, I always try to use good grammar and proper punctuation in emails and texts. My communication style is pretty formal and polite. I’ll loosen up a little once I get to know the client but it’s important to always be clear and direct so that everyone involved with the project is on the same page. Also, I like to keep the client posted with updates as the shoot unfolds and wraps. Most of the time things happen as planned but in the event that something unexpected occurs it’s always a good practice to let the client know as soon as possible so that we can create a solution.

EG: I think it’s really important to remember that you are 1 of many dozens of emails they get per day. Say what you gotta say. Be respectful of their time, let them be impressed (or not), and keep it moving. Also, make things easy for them. Make sure the links are easy to navigate, no mistakes, etc. Here’s a pretty basic example of an email I might send:

CC: When it comes to outreach and sharing new work, I think every editor and art buyer likely has a personal preference on the frequency of communication. Personally, I don’t reach out more than once per quarter with relevant updates nor do I expect a response. I trust that if they have the time or desire to respond, they will otherwise I’ll assume they looked at my email and will reach out when the right project comes along. If they responded to every email they received from a photographer they probably wouldn’t get any work done. As far as etiquette, I’m pretty similar to Jared in being polite, formal, and brief. I think there’s a time to be professional and when you establish a relationship with them and get to know them and their vibe it’s easier to be candid and casual. I’ve gained a lot of perspective from listening to Dear Art Producer (thanks Heather Elder!).