Questions

Knowledge Base Questions

JS: A successful personal project, from my perspective, should be about something or someone that you care about, it’s much easier (and exciting) to make photographs when you are invested in that particular topic, issue, or community. The project should be a vehicle to showcase your aesthetic and the images should be presented the way that you see fit. It should also be about discovery, you should be learning during the process. A printed piece, a pop-up installation, a project-specific website, a hashtag, are a few examples of ways to present and distribute a body of work. Field time for my projects has varied based on the topic: 10 years, 2 weeks, and 2 days. Time is always a good thing but it doesn’t always result in a worthy project.

Self-initiated projects represent who I am as an artist. This type of work is the foundation that drives me to make photographs. Small Town Hip hop, The Farms, and The Skaters of La Paz are all examples of my personal work.

EG: Beyond what JS said, it should ideally represent the type of work you want to make. Every assignment will have an agenda that isn’t necessarily your agenda. A personal project should be 100% about your agenda.

CC: One project I found to be successful because I was able to demonstrate a new approach to lighting in studio. Another project was successful because I was able to tell stories and create images and compile them into a self-published book that I wanted to see exist in the world. Another was successful because I was able to stretch myself and direct, DP, and edit a motion piece. All this to say, I have found success in personal projects when I felt that I was able to do something different from what I typically do when I’m commissioned and stretch myself to apply a new skill or create something I hadn’t done before. I think a personal project is successful if it yanks you out of complacency to create work that tells people more about you (personally/stylistically/artistically). Naturally, this will be something you’re excited to share, and maybe someone will see it, be inspired by it, and hire you to create something similar for them. But, I see this as a bonus by-product of the project and it’s not my motivation because what if you don’t receive any response?

Link to this anwser.

EG: Research! Who are your peers? Who has the career you want? Who hires them? Who do they follow? What clients will realistically hire you? Follow all of them and try to befriend them all. Don’t be annoying. If you do it right, you’ll start getting calls. It might take a few years, but keep doing it. HEAD DOWN. KEEP MOVING FORWARD.

JS: All of this info is at your fingertips these days- Google, Instagram, and LinkedIn (yeah I know it’s a bummer of a site but it’s pretty useful these days for figuring out where people are working). If you’re able to answer these questions “what’s your work about and who are you trying to reach” you will be able to put together a shortlist that you can follow on socials or reach out directly and politely to on IG.

CC: It was helpful for me when I sat down a made a shortlist, like Jared suggested, of the brands and publications I wanted to work with and why or specific categories of clients you want to work with. From there, look for art producers, art buyers, art directors, photo editors, photo directors, etc. The internet is your friend. It also doesn’t hurt to ask for introductions or referrals from existing contacts.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Being a photographer is like 25% taking photos and 75% building a network and letting people know you exist. If you’re not committed to that 75%, you’re not doing it right.

CC: I do this by actively sharing it with people or trying to get published in places where more people are looking. If I want new people to see my work, merely sharing it on your IG and website won’t suffice. As Emiliano said, the act of getting your work seen is active work. Who am I directly sending this work to who would appreciate it? Specific photo editors at places that publish this type of work? Specific art directors/buyers who have clients in this category? Art blogs?

Link to this anwser.

EG: I always think that whether you can figure out how to start assisting is essentially a litmus test of whether you’re gonna make it or not. The formula is pretty easy, tbh.

1. Find photographers you like.

2. Email them. Say hello. Tell them you like their work and you’d love to assist someday.

3. Don’t expect a response. If you get one, great.

4. Stay in touch a few times a year.

5. Repeat until you no longer want to assist.

There it is. That’s the secret to a career in photography. Research. Interact. Repeat. This works for assisting, for magazines, for commercial clients, etc etc. If you’re cool, or talented, or a hard worker, or really pleasant, or any combination of those, you’ll be fine if you follow this formula.

JS: An easy way to get started is to assist your friends, you will both learn quite a bit in the process and it’ll be low pressure since you know each other. Another way is to reach out to photographers in your area. Send them a polite email sharing your background and experience level along with a link to your website, conveying your interest in assisting. Join a professional organization such as ASMP or APA both have databases for assistants.

CC: Do what is suggested above and follow up. I started assisting by doing 1, 2, and 3. I’ll also add that I didn’t get any responses from the 30+ emails I sent and when I followed up with all of them I received a response from 2 people who I ended up assisting regularly for two years and learned a ton from (while also testing and assisting my friends – make friends with other photographers at your level at local photo events and you’ll level up together as time goes on). As Emiliano said, it’s important to stay top of mind and if a photographer’s usual assistant isn’t available and you happen to follow up on your email, you might get hired. The tricky part is not having all the experience necessary (or any experience) to be a first assistant so Jake Stangel created this super helpful video. I’d have to say that nothing compares to being able to play with all the gear IRL so I would also suggest reaching out to 1st assistants and asking if you can be brought on as a 2nd or 3rd assistant on bigger jobs. I learned so much this way – during downtime, the 1st assistant would show me how all the gear worked. You can also try to get into the equipment rooms at studios or rental houses to familiarize yourself with the gear and meet photographers that way.

Link to this anwser.

EG: The standard is a website plus an IG presence. BUT. If your work really can benefit from some non standard presentation, then by all means.

For in person meetings, almost everyone has a portfolio (of varying price points) or a tidy digital presentation (ie iPad). It doesn’t need to be a custom $400 portfolio either! As long as you show that your photos are technically sound and you’re capable of building cohesive bodies of work, no one really cares if the portfolio itself cost $50 or $500. Also, I know several photographers that would come to meetings with a box of prints. If that feels better for your work, then go for it. But please remember if your presentation is too kooky, then you’re taking attention away from your photos. For reference, this is my current portfolio.

For online presence, a website is essentially a must. I’ve seen people get hired from tumblr pages and other alternative forms, but that was before website got really easy to construct. The current version is people with only an IG presence and no website. The people that can pull that off are prolific and very talented. They are the exception to the rules.

Another quick note about websites. Display your best work only. I think most people would rather see only 5 great images than 5 great images among 20 mediocre ones. This is painfully common. No one wants to see some e-comm photos of bags just because you think it shows you’re a “commercial photographer!”

JS: Short answer: YES. A dedicated website to display your photography the way that you want to is crucial. Additionally, this space on the web will be what people in hiring positions use to reference your work. Pre-Pandemic, I would have highlighted the value of a physical portfolio but since we’re still living in amidst Covid, I don’t think it is necessary because in-person meetings are not taking place. Another approach would be to make a PDF portfolio that could be shared directly with an editor or art buyer.

CC: I think you need a website because it’s a different way to experience and present your work than IG and likely the best format for your work to be seen (thinking of landscape images across three carousel posts on IG). The way you design your site can also tell people more about you and your style. The same goes for your printed portfolio for in-person experiences.

Also, this note was submitted to our site –

Link to this anwser.I beg of you to please tell photographers to put their contact information on their websites. Phone number and email. Get a google voice number if you don’t want your info out there.

But I beg of you, HELP ME HIRE YOU. PUT AN EMAIL AND PHONE NUMBER ON YOUR SITE.

AND TELL ME WHERE YOU ARE.

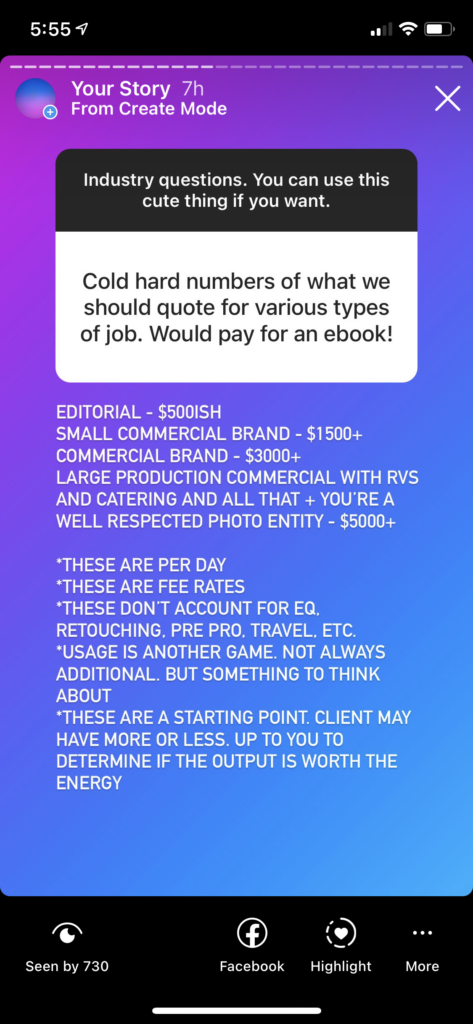

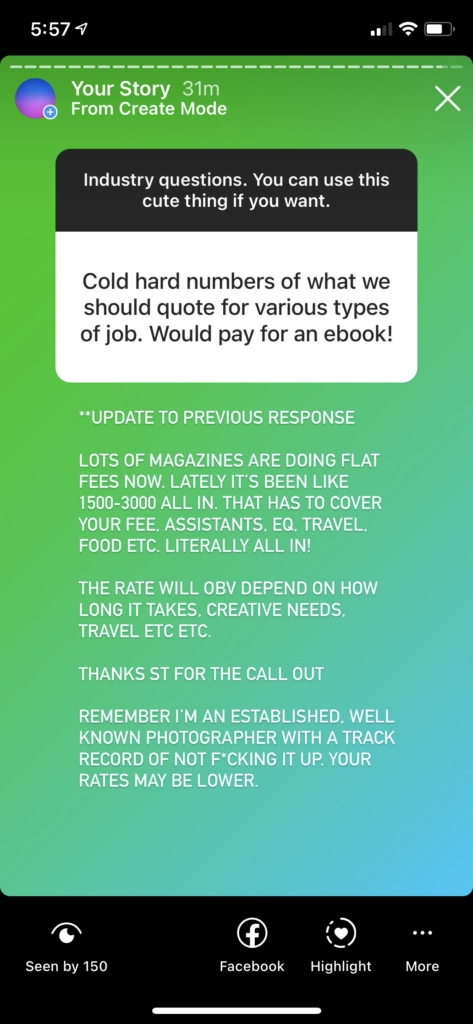

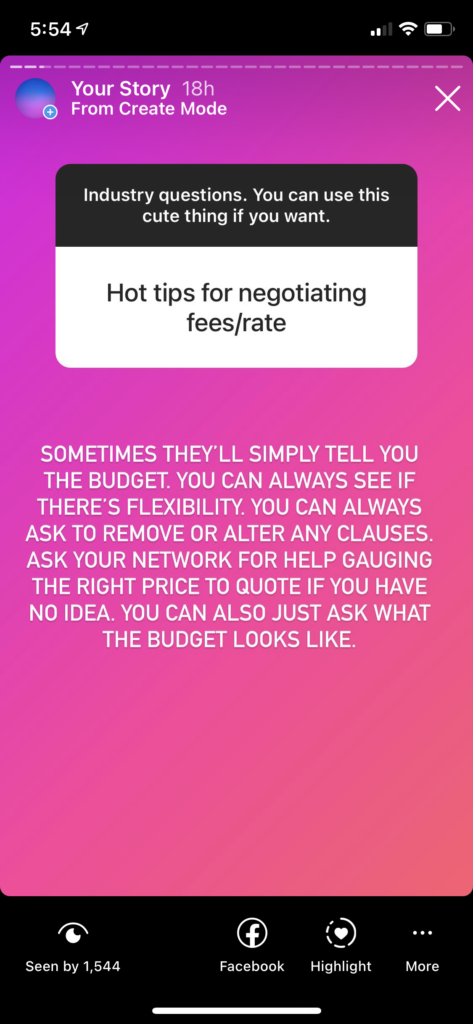

JS: For editorial, the rates are set by the publication and they can fluctuate from $500 to $1500 not including expenses (travel, meals, assistant, equipment, etc). In terms of commercial projects, the rate should be dictated by the usage- the more usage, the higher the rate- again not including expenses.

EG: From my IG stories.

CC: The numbers that Emiliano shared above are spot on based on my experience. If a client asks you this question, my next questions are always “Can you tell me how many images will be delivered, how and for how long the images intend to be used? Is there a budget outside of the day rate for expenses (assistant, equipment, retouching, etc.)?” Ask for help and make sure it’s a fair exchange.

Link to this anwser.

EG: Don’t. If you can avoid it.

Obviously, sometimes you gotta take the money or the project is something you really want to do. Try to negotiate and ask if there’s any flexibility on the terms or the budget.

JS: Contracts are always negotiable. Do the best to communicate that the terms are uncomfortable and overreaching, then propose a new set that are more favorable to you. Also, it’s more than okay to walk away.

CC: Sometimes clients want a buyout of images or WFH so they don’t have to deal with licensing. There’s an opportunity to ask how the images will really be used and negotiate to keep the copyright and discuss licensing. You get to decide whether it’s worth losing out on any opportunity for a license extension in the future or to license the body of work to a third party in the future. Some great advice here from Photo Bill of Rights.

Link to this anwser.

CC: Having an agent is the key to booking jobs. At least that’s what I thought when I was starting out. Instead of looking for jobs, I was looking for an agent. The question to ask yourself first is, do you need an agent? Do you have the portfolio and the commercial experience that an agent can confidently get behind? Are you working so much that you’re missing out on opportunities while you’re on set?

You can absolutely get commercial work without being represented. You’ll need to learn how to negotiate and put together bids. Having an agent doesn’t guarantee you’ll be getting jobs – it really depends on how hard your agent works, their reputation and network, and how hard you’re working to facilitate what they do and what you’re doing (personal work, newsletters, promos) in tandem with their efforts.

Also, photographers pay their agents a commission (typically 20-30%) whether or not the job came through the agent. The only exception to this is if the client is on a pre-existing house client list that your agent approves prior to you signing. My agent solely focuses on commercial opportunities so I am still doing my own marketing for editorial work. If you are at the stage in your career where you can manage doing what an agent does on your own or paying a consultant to help for an hourly rate rather than a % of your fee, does it make sense for you to have an agent? If it does, then go ahead and start sharing your work with agents and build relationships with them the same way you would with a client. Get to know them and work on a few jobs together to see if they’re a good fit. They become a big part of your brand. Listen to this podcast starting at the 27min mark to get a better idea about the thought process from an agent’s perspective.

JS: Photography is all about relationships and this applies to working with agents too. I realized that I needed the help of an agent when I noticed that commercial agreements were beyond knowledge of contracts and that the negotiation process required a significant time investment. Additionally, I was starting to get busier with both commercial and editorial work along with maintaining my personal practice as an artist. My thought process was that I needed to find an agent who could take the business side off my plate so that I could focus more on the creative. The way that I started the search was to reverse engineer it, I was interested in seeking out agents that had preexisting relationships with brands and ad agencies that I had already worked with or desired to collaborate with in the future. So I did the breadcrumb trail thing and paid attention to who photographers were tagging in their social posts. Also, spoke to a few photographers who had been represented and got their takes. I made a list and contacted a few to introduce myself and then followed up when I had jobs that made sense to bring an agent onboard. Working with an agent on a nonexclusive basis is a good way to get to know them and how you both work together. This process is a lot like dating, it’s slow and it should be.

And here is a pretty extensive list of photography agents by APhotoEditor, here.

EG: The short answer is, if you have to ask, you’re not really ready for an agent.

The longer answer involves lots of hard work, establishing yourself as a name, tons of introductory emails, networking, meetings, successful projects, a good reputation, some positive energy behind you, etc etc. Carmen and Jared hit up most of the points above. But tbh, if you don’t know how to research, network with and get the attention of agents, then you probably haven’t learned how to research, network with and get the attention of clients, yet. It’s essentially the same thing just with a different set of people.

Additionally, once you’re ready, agents will start to say hello and show up in your social media, etc. Of course you should be proactive in letting them know you exist, but their literal job is knowing whats hot. And if you’re hot, then they’ll find you.

Link to this anwser.

CC: I still struggle with doing this on my own but here are some resources I’ve found:

A Photo Editor – $free – use the search function to find relevant examples like “pricing buyout” “pricing social media” or browse through to see the thought process and context for commercial estimates. I used to cobble together estimates using these examples.

Wonderful Machine or other Consultants – varies, WM is $150/hour, they take over the estimating process on your behalf.

Photo Agents – $free initially, 25%-30% commission if you win the job, they take over the estimating process on your behalf.

Getty Images Calculator – on the high end and doesn’t consider volume since you’re calculating a single image price.

fotoQuote software – $150 one time purchase – industry-standard photo Pricing Guide with licensing

Blinkbid software – $16/mo or $168/year subscription – bidding, producing, and invoicing

JS: In addition to the resources that Carmen shared, another approach is to ask if the client has a budget in mind. If they do then you can take that number and run it through the calculators above and or your personal network to arrive at a fee based on the usage.

EG: Everyone struggles with this! But let’s think about this pain as an opportunity to unpack why it’s so hard, though. I think the pain is not really about choosing the best photos. The pain is about figuring out ‘Who am I and what do I want to say?’ So when editing down your pile of photos, repeatedly ask yourself “Who are you and what do you want to say? Does this image support or enhance that vision I want to create?”

Here is a clip of me talking to one of my mentees about the difficulty and the value of editing your portfolio. Sorry I’m not as beautiful as young Leo.

JS: I really want to drop an updated version of the Ernest Hemingway quote about writing and bleeding at a typewriter. In all seriousness, editing can be a difficult and often lonely task. As I write this, I’m trying to motivate myself to put together a new edit of some portrait work over the past 2 years. I share this to say that even 10+ years in the biz, the task of breaking apart my work, figuring out what is successful/unsuccessful is still daunting and challenging. Beginning the process of editing is a lot like trying to floss daily or even jogging, both of these are activities that you don’t really look forward to but you know that they’re necessary. For me, I like to start with a couple of questions- “What’s this work about, and what do I want to say?” Be ruthless with your image selection- “does this image help advance your story/aesthetic?” LESS IS MORE. Having 8 incredible photographs with a consistent aesthetic will always better than a potpourri gallery of 17. Good editing takes time. Rome wasn’t built in a day and neither will your portfolio. Set a realistic deadline so you don’t put off this process. Do a little bit here and there, hit up a peer or 2 and over time the work will let you know when it’s ready to be out in the world.

CC: Because we’re often emotionally attached to our work and we know what it took to make certain images or think that a certain image should be included for whatever reason. I love the advice Emiliano and Jared gave above. Also, about 5 years into my career I hired someone to help me edit my portfolio. It was interesting to see what they ended up with and they noticed through-lines in my work to help it feel cohesive in ways I didn’t. In hindsight, I was at a point in my career where I wasn’t sure what I wanted to say and I let the editor mold my portfolio into what they thought it was saying which was helpful at the time. Since then I’ve had good and mediocre experiences with hiring editors and my friends have as well. Take any feedback and advice with a grain of salt, everyone’s opinion about your edit will be subjective. You know what you want to say best so if you work with an editor, make sure this is clear to them or you’ll have a frustrating experience. Think about what you want to say and where you want to go with your career and ONLY show the work that demonstrates this. Eliminate redundancy, your portfolio needs to be a succinct edit that also shows the breadth of your skill and clearly communicate your style. If something doesn’t fit in with the rest of your work it’ll only confuse people or dilute the existing work.

Link to this anwser.